Introduction

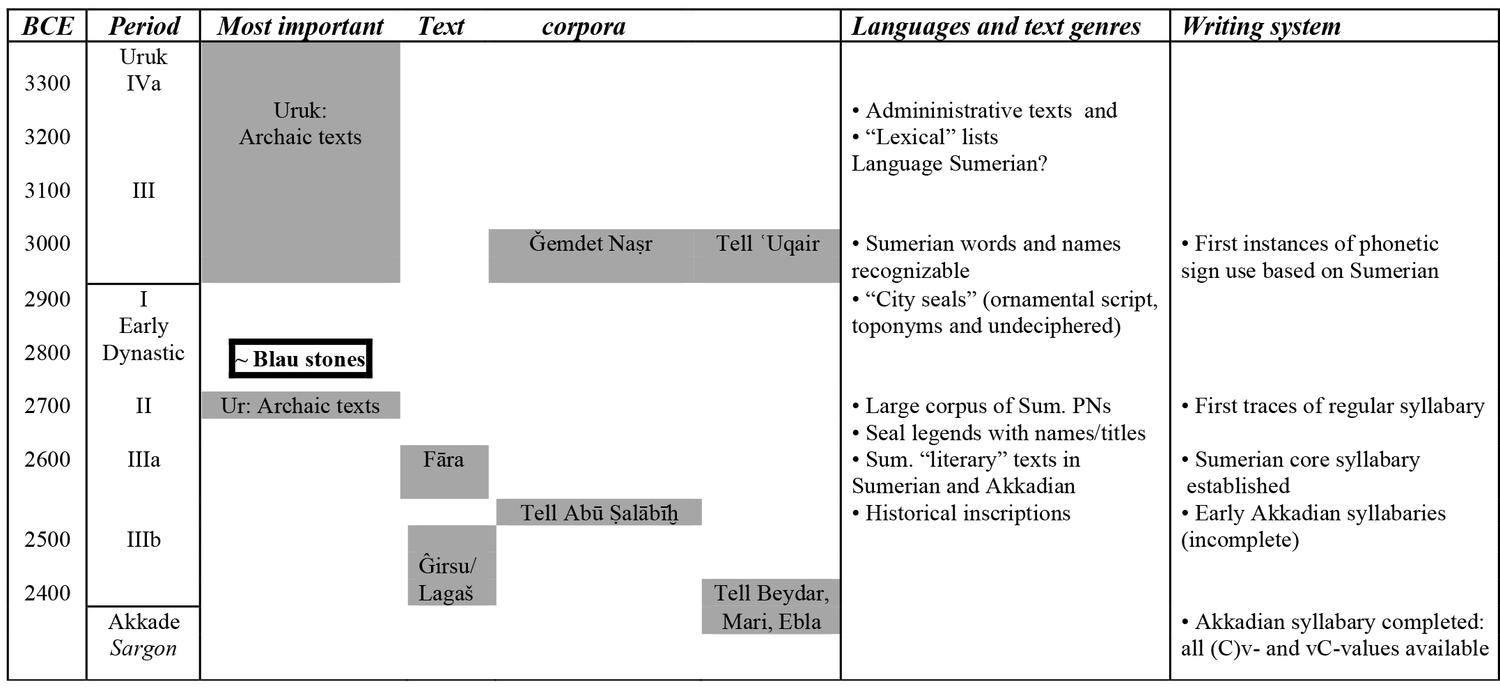

Discussing archaic cuneiform texts with my friend Peter Damerow was one of the most exciting aspects of my visits to the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Peter was primarily engaged in deciphering the numeral and metrological systems attested by the earliest cuneiform texts (ca. 3300–3000 BCE, see fig. 4.1), and in reconstructing their administrative and social background. But he was also interested in the history of writing in general, and in the history of the cuneiform system in particular. Peter and I focused on different—but adjoining—periods within the early history of cuneiform. When I received the invitation to the colloquium commemorating Peter Damerow, on which this volume is based, I considered writing about the unusual early cuneiform documents which both Peter and I had studied: the so-called “Blau Monuments” or “Blau Stones.” These are two stone objects of different shapes that bear archaic cuneiform inscriptions and reliefs. For their historical context, see fig. 4.1.

Fig. 4.1: The chronological context of the “Blau Stones.” MK.

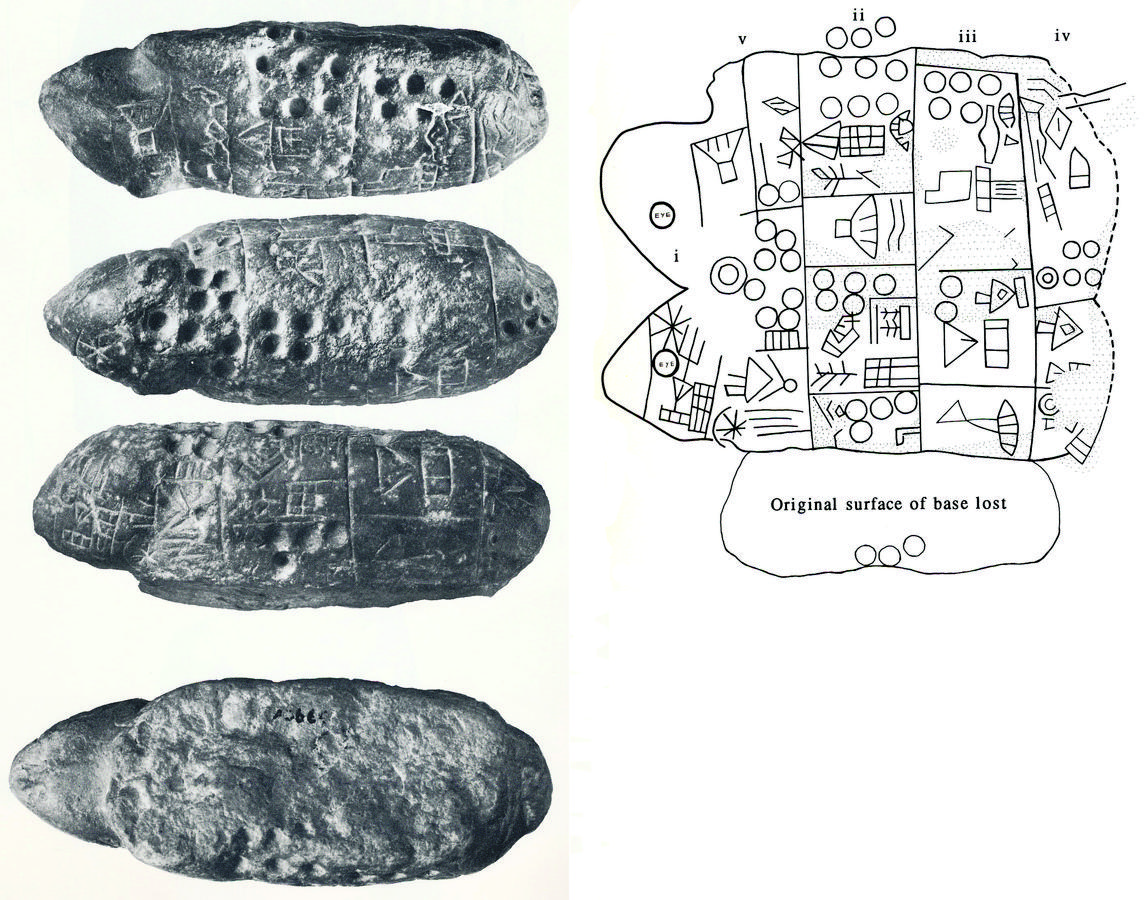

The first one is called the “obelisk” (see fig. 4.2). In accordance with the orientation of its relief (and with the later direction of writing), the triangular shaped end is regarded as its top. The second one, which has a roughly semicircular shape, is called the “plaque” (see fig. 4.3). The obelisk measures 18 × 4.3 × 1.3 cm, and the plaque 15.9 × 7.2 × 1.5 cm.

Fig. 4.2: The “Blau Stones”: obelisk. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 11).

Fig. 4.3: The “Blau Stones”: plaque. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 12).

The two pieces were allegedly bought in the vicinity of Uruk by their first, eponymous owner, Dr. A. Blau, who lived in Baghdad. In 1889, they were donated to the British Museum where they are registered as BM 86261 (obelisk) and BM 86260 (plaque), respectively. Since their publication in 1985 by W. H. Ward, they have raised much discussion and there have been many attempts to interpret them. Initially, even their genuineness was disputed (Ménant 1888, 69–88). Up to now, only several textual units—the term for “field,” numerical signs, and quantified commodities—are identifiable with certainty, and a coherent interpretation of both documents together is still lacking. The two main difficulties are the correct interpretation of signs and the establishment of their correct order. The archaic sign repertoire was much larger than the later one. During the early phases of cuneiform many signs fell out of use, merged, or changed their shape. Until approximately 2500 BCE, signs were arranged freely (i.e., not reflecting linguistic serialization) within each case or line,1 except for numeric signs, which were always placed first.

Most Recent Editions

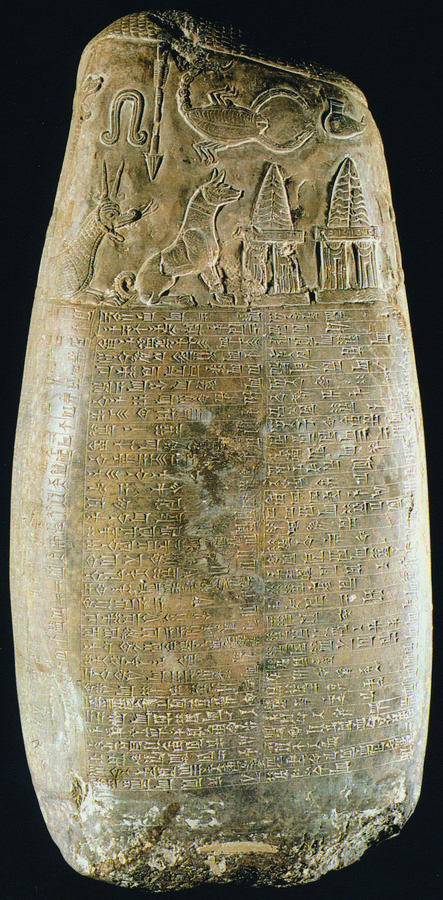

The most recent editions and studies of the text on the Blau stones are Fenzel (1975) and Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991) (ELTS), no. 10–11 (with comprehensive bibliography). A new transliteration along with the copies of ELTS can be found in CDLI (ID numbers P005995, P005996). Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991) incorporated the Blau Monuments into a group of archaic documents, which they dubbed “ancient kudurrus.” The Akkadian term kudurru2 originally referred to much later monuments (fourteenth–seventh centuries BCE), most of them inscribed with royal land grants; an example is given in fig. 4.4.

Fig. 4.4: Middle Babylonian kudurru from the reign of Marduk-šāpik-zēri (1080–1068 BCE). From Hrouda (1991, 154).

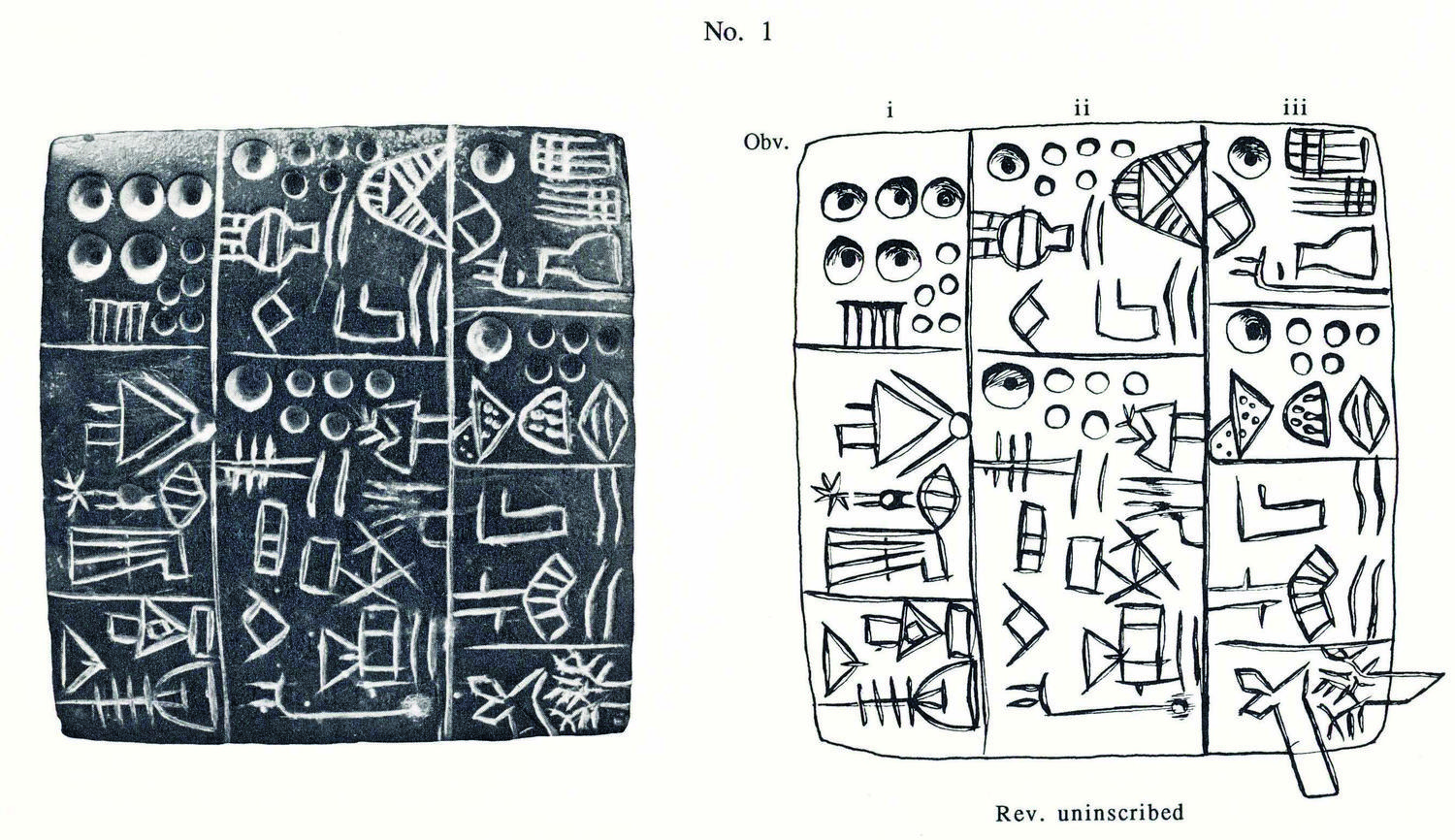

As a rule, the later kudurru texts start by providing the measurements of a field and describing its location. This seems to apply cum grano salis also to the “ancient kudurrus.” The cuneiform character GANA2 “field” and the numerical signs referring to it are easily recognizable on top of the Blau obelisk and other “ancient kudurrus.” Most of them are rectangular stone tablets (ELTS 1–6, no. 1 is shown in fig. 4.5) made of different material than the usual administrative tablets of clay, but some exhibit peculiar shapes such as that of a sheep or a lion-headed eagle (ELTS 8–9, no. 8 is shown in fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.5: “kudurru” from the Uruk III period. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 1).

Fig. 4.6: “kudurru” from the Uruk III period. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 6).

Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991), following the communis opinio, dated the “ancient kudurrus”—including the Blau monuments—to the Uruk III or Ǧemdet Naṣr period (around 3000 BCE). The most recent archaeological study devoted to the Blau Monuments, Boese (2010), deals mainly with their dating. Boese quotes an article by P. Damerow and B. Englund (1989) that already expressed their doubt about the conventional dating of the monuments. Based on a more detailed paleographic analysis and adducing comparative iconographic evidence, Boese argues for a later date (Early Dynastic I). This seems to be contradicted, however, by the main figure of the relief on the plaque, the so-called “priest-king” with his characteristic “net-skirt,” cap, and beard, since there are close parallels among pictorial representations, mainly on cylinder seals commonly dated to the Uruk III period and even earlier. Boese (2010) formulates the problem and its possible solution as follows: “Do these seals—and perhaps also the famous Warka-Vase with comparable pictures—equally stem, like the Blau Monuments, from the next younger phase (ED I), or did there possibly exist an unbroken tradition in theme, style and iconography, reaching from the last phase of the Protoliterate to the first stage of the Early Dynastic Period? The first alternative seems to me the more probable answer, though it cannot be proved definitely.” Concerning the iconography, Boese points out that the object in the hands of the “priest-king” on the plaque is most probably “die Wiedergabe eines hohen, schlanken Gefäßes vom Typ der Warka-Vase,” and that the person facing him is more likely male than female. He also addresses questions of whether the two stones really belong together, and if their inscriptions could have been added later, as suggested in Nagel, Strommenger, and Eder (2005, 11). As to the second question, he plausibly argues that the arrangement of the reliefs and the inscriptions speak in favor of their contemporaneity. As to the interrelationship between the two monuments, he repeats the obvious arguments for their belonging together: identity of material, uniformity of style, motifs, and paleography. Furthermore, he quotes an observation which I made in my review3 of Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991) and builds upon it another possible argument for their interrelationship. While I had compared the peculiar shape of the obelisk to the early form of the cuneiform sign KU representing the Sumerian verb dab6 “to seize, to take,” Boese proposes a corresponding interpretation for the plaque by comparing it with the cuneiform sign BA which represents the Sumerian verb ba “to allot, to assign.” The two signs are illustrated below (see fig. 4.7, left) in a single archaic administrative text from the Uruk III period; a similar tablet from the same period (see fig. 4.7, right) already contains the younger, simplified form of KU.

Fig. 4.7: Variants of the sign DAB5 in administrative texts from the Uruk III period. From Seipel (2003, vol. IIIB, p. 37, no. 3.1.27, and p. 35, no. 3.1.25b). Sign names added by MK.

It seems noteworthy that the inscriptions on the two Blau Monuments show a clear distribution of contents: The obelisk deals with the field, whereas on the plaque quantified objects are listed, which are presumably gifts in exchange for the field. Boese does not cite an older hypothesis concerning the shape of the Blau Monuments: In 1961, M. E. L. Mallowan compared the obelisk to a craftsman’s chisel and the plaque to a pottery scraper.4 This hypothesis deserves to be reconsidered in the light of my present contribution, in which I suggest that the Blau monuments refer to a transaction by “stone-cutters,” that is, craftsmen who make use of similar tools.

Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991) postulate a northern provenience for the “Blau Stones” on the basis of the possible toponym Urum in lines 2–3 of the obelisk, while Boese maintains that they most probably stem from Uruk because depictions of the “priest-king” are best attested there.

On the obelisk, which is inscribed only on one side, the lines run from top to bottom (= right to left according to the archaic direction of writing), and their order is unambiguous. The inscription of the plaque is more complex, but the order of columns and lines can be established on external and internal grounds with a high degree of certainty. The reliefs divide the inscription into four sections. Section 1: The text starts on the fully inscribed side (called “obverse”) with two horizontal rows of lines called “columns” according to the later direction of writing which implies a counter-clockwise rotation of 90%. Section 2 consists of three lines between the two standing persons (counted from top to bottom = left to right according to the later orientation). Section 3: The text continues in the back of the left standing person with two rows or columns running smoothly around the edge to the other side of the plaque. They end behind the back of a sitting person. Section 4: The signs in front of the sitting person constitute the last section of the text. Somewhat problematic is the role of the last signs in the two columns: do they constitute separate lines (with the edge functioning as line divider), or are they continuations of the last lines on the obverse? Concerning the left column, internal reasons speak clearly in favor of the first possibility: The last line on the obverse as well as the first line on the reverse contain a numerical sign like the preceding lines and the following lines (in the second column on the obverse). The end of the second column will be discussed below in connection with the structure of the text as a whole.

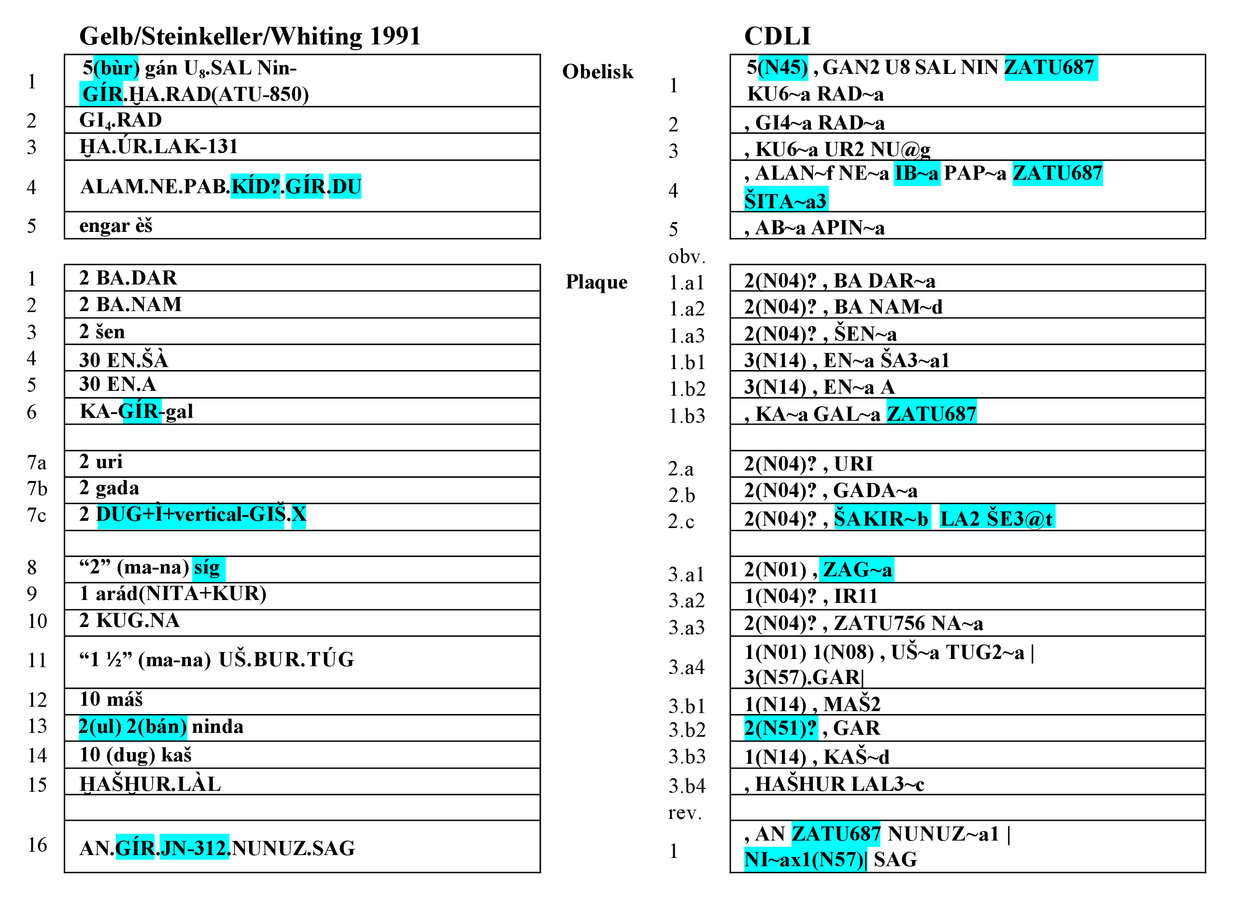

In my present contribution, I would like to suggest some new readings and interpretations in the hope that they may stimulate further discussion and progress. Let me show you first a synopsis of the two most recent editions of the text, Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991), and CDLI (see fig. 4.8):

Fig. 4.8: The text of the “Blau Stones” in recent transliterations. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, 43); CDLI, nos. P005995, P005996.

Both editions correspond as to the order of sections and lines. The transliteration in CDLI is more abstract, more cautious, and more detailed with regard to paleographical features. Some signs—highlighted blue in the synopsis—were identified differently in the two editions.

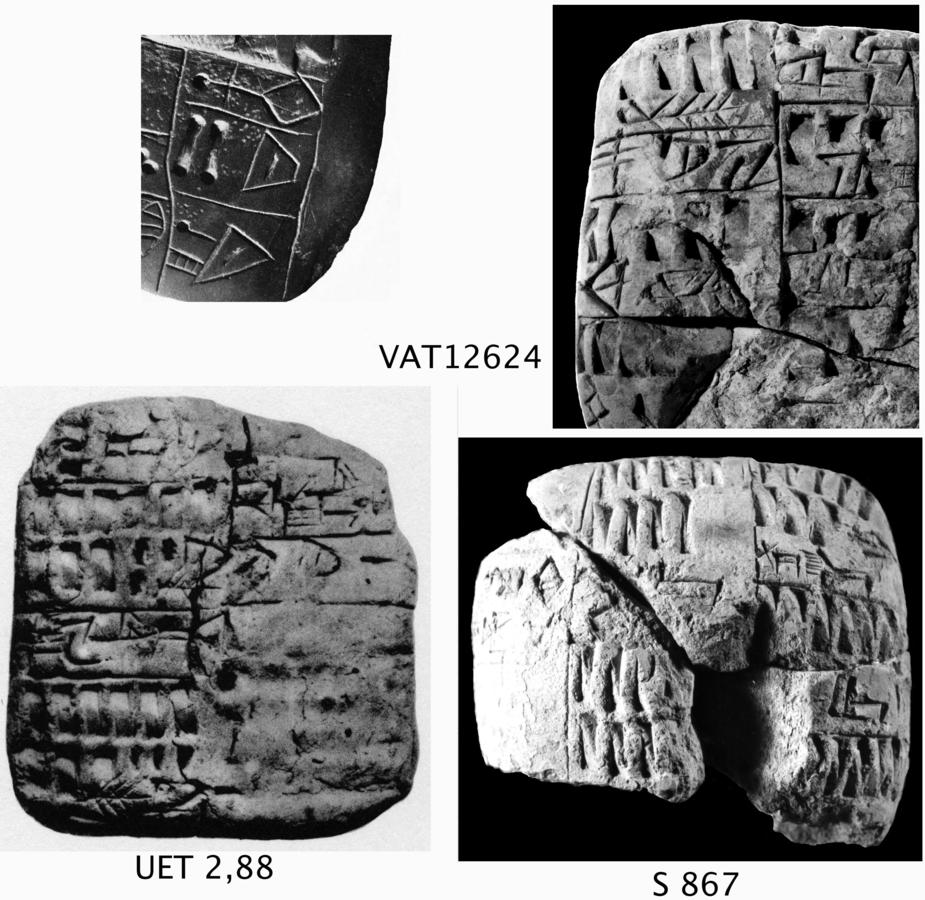

The first discrepancy in line 1 of the obelisk shows that the interpretation of the numerical signs is in some cases doubtful. This is particularly the case with circular signs which vary in size. On clay tablets, a small circular stylus impression represents u “10” or 1 bur3 (a surface measure, ca. 6.5 ha), a big one šar2 “3600” or “60 bur3.” The 5 circular holes referring to GANA3 “field” at the beginning of the obelisk inscription are interpreted as “5(bùr)” in ELTS, and 5(N45) = 5 × 60 bur3 in CDLI. On the plaque, the holes in lines 4–5 = 1.b1–2 are wider than those in 12 = 3.b1 and 14 = 3.b3, but are interpreted uniformly as “10” in both editions. The numerical sign in line 13 of the plaque is read 2(ul) 2(bán) in ELTS, but 2(N51)? = 2 × 120 by CDLI. The latter interpretation is certainly correct, since similar forms can be found in the archaic texts from Ur and in the Fāra texts (see fig. 4.9):

Fig. 4.9: Early forms of the cuneiform sign for “120.” From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 12); Burrows (1935) (UET 2); photographs by O. Teßmer, Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin (VAT 12624) and H. Steible, Freiburg (S 867).

In line 4 of the obelisk, the two editions differ in the reading of three signs. The sign tentatively read “KÍD?” in ELTS was correctly identified as IB already by K. Fenzel. The identification of the sign read GIR2 in Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991) and earlier editions (which I had already doubted in my review) was given up in CDLI, and the sign in question is transliterated ZATU687.5

In line 7c = 2.c of the plaque, the difficult signs following the number are transliterated DUG+Ì+vertical-GIŠ X in ELTS and analyzed as ŠAKIR~b LA2 (+) ŠE3-tenû in CDLI. The first of the two signs seems indeed to represent a vessel, and the inscribed NI could specify it as an “oil” (NI = ì) vessel as suggested in ELTS. The association with later sign and term ŠAKIR “churn” is, however, uncertain. The following graph (X in ELTS) is split up into LA2 and ŠE3-tenû in CDLI. This seems plausible since the two signs may be interpreted as “tied (LA2) with a rope (ŠE3-tenû),” which is a possible specification of a vessel.

The unclear sign in line 8 = 3.a, is better identified as SIKI (SIG2) “wool” (ELTS) than ZAG “side” (CDLI) because the context requires a quantifiable commodity.

The analytical transliteration |3(N57).GAR| (CDLI) for BUR (ELTS) in line 11 = 3.a4 is highly artificial; it is by no means clear that BUR goes back to such a combination of signs.

Some New (and Old) Sign Identifications

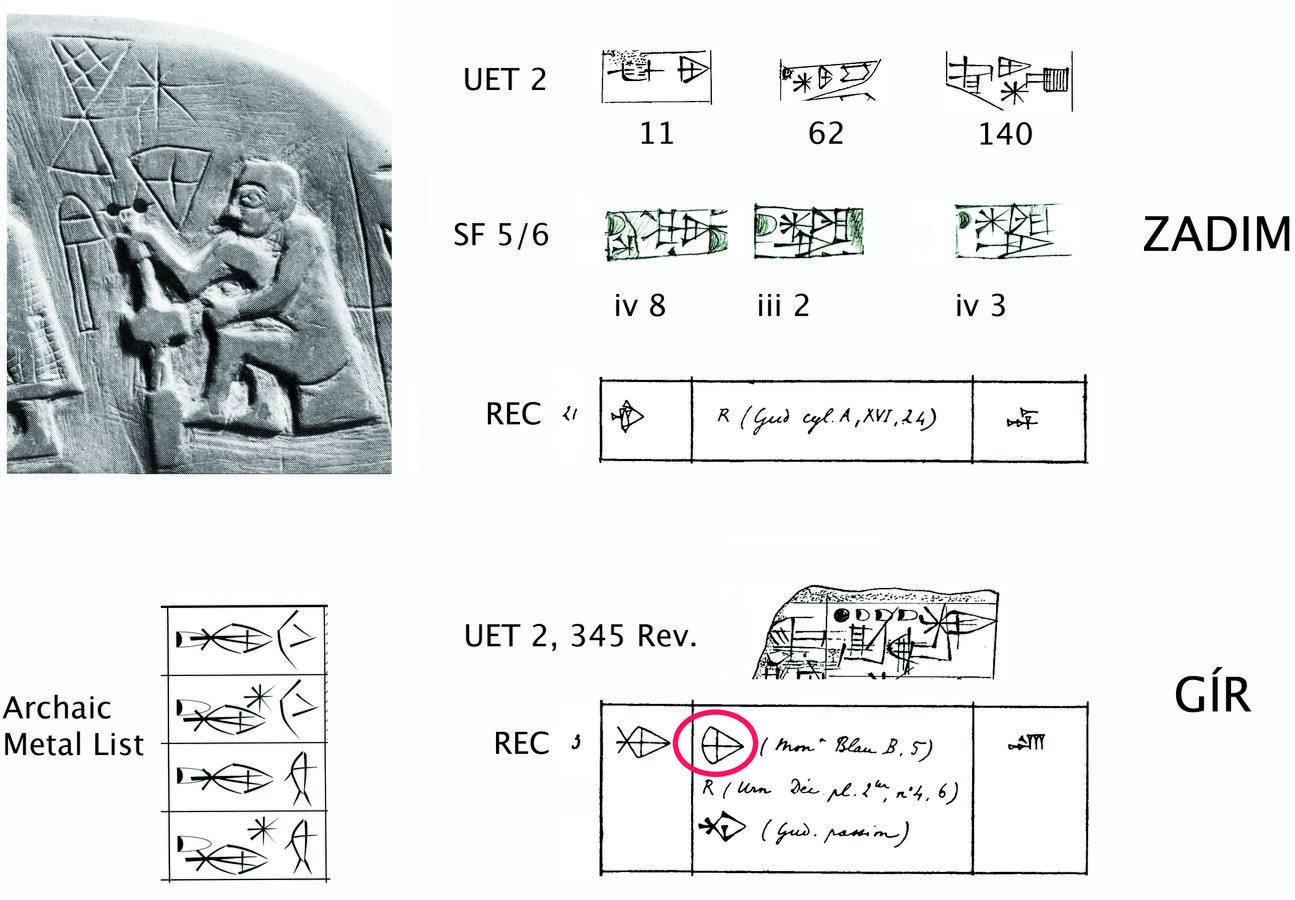

Because ZATU687 and two other signs were read differently in ELTS and CDLI, I would like to suggest interpretations of my own. Allow me to first show my transliteration and structural analysis of the text (see fig. 4.10). I have rendered the numerical signs by n and index numbers according to their first occurrence in the text: n1 = circular hole, n2 = horizontal, (approximately) semicircular hole etc. The different sizes of n1 are symbolized by the letters a–d: n1a, n1b, etc. The newly suggested readings are marked by different colors.

Fig. 4.10: The text of the “Blau Stones”: structural analysis. MK.

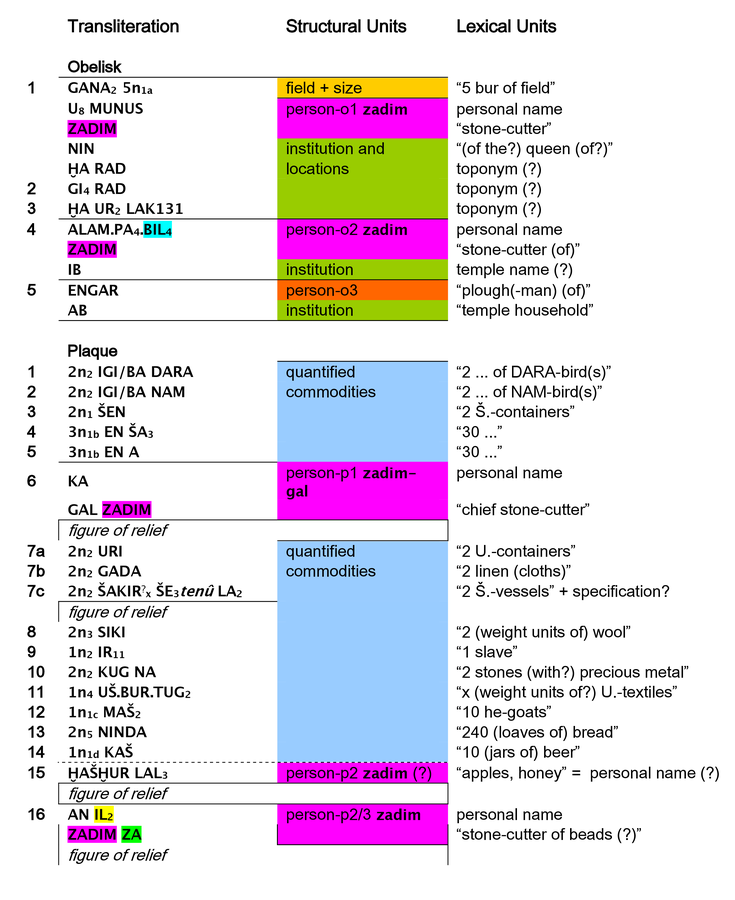

ZATU687 = ZADIM/MUG

Occurring twice on each stone, ZATU687 is the most frequent sign in our text. The observation that it is a relatively rare sign in the entire corpus of archaic and Early Dynastic texts supports the suspicion that it might be the key term of the document. Already in the earliest editions, it was read as GIR2, an identification which I doubted in my review of ELTS. I would suggest now that ZATU687 is a precursor of the later signs ZADIM and MUG. To my knowledge, ZADIM and MUG were not yet differentiated during the Third Millennium. In later periods, a distinction seems to have been introduced only in the Assyrian ductus. ZADIM was clearly distinguished from GIR2 during all periods (see fig. 4.11). Nevertheless, F. Thureau-Dangin in his sign list Recherches sur l’Origine de l’Ecriture Cunéiforme (REC) from 1898 included the ZADIM of the Blau stones under GIR2, an early error which might have influenced later studies and editions of the Blau monuments.

Fig. 4.11: Early forms of cuneiform signs ZADIM and GÍR. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 12); Burrows (1935); Thureau-Dangin (1898, 1, 5) (REC); Englund, Nissen, and Damerow (1993, 32) (Archaic Metal List); MK.

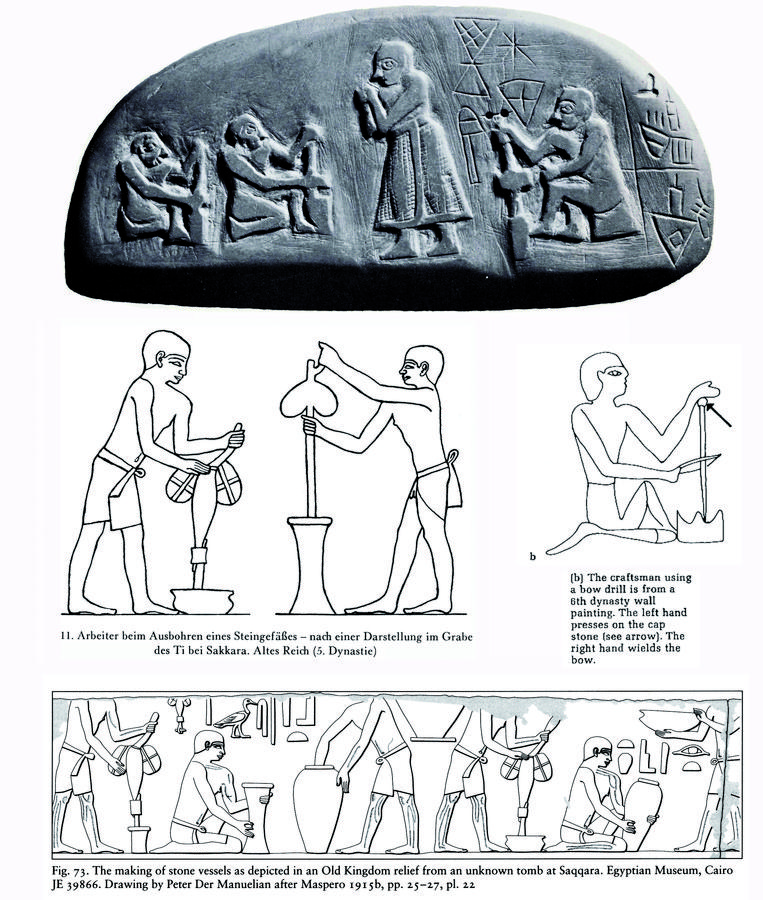

The reading mug occurs mostly in the name of the goddess dNin-mug and as a designation of wool of lesser quality (= akk. mukku). Since ZATU687 and NIN co-occur in the first case of the obelisk, the two signs could in principle represent the divine name Nin-mug. ELTS assumes a divine name “Nin-GÍR.ḪA.RAD” which “could very well be a goddess of [the city of] A.ḪA.” However, in view of three more occurrences of ZATU687 in varying contexts, it seems preferable to consider “GÍR” = ZATU687 here as an isolated element. The reading zadim designates a craftsman, namely a “stone-cutter.” The term seems to be composed of za “stone” and dim2 “to make, to fashion.” It can be compared with ku3-dim2 “silversmith” or “goldsmith,” an analogous compound of ku3 “precious metal” and the same verb dim2. If our identification is correct, and if the sign is indeed a key term for the whole document, one is tempted to connect it with the reliefs. It is impossible to cite and discuss here the many differing descriptions and interpretations of the persons, objects, and activities depicted there. My own suggestion, based on the identification of zadim as “stone-cutter,” at the time seemed new to me, but I recently discovered that Eva Braun-Holzinger’s book on Das Herrscherbild in Mesopotamien und Elam (Braun-Holzinger 2007) also contains a chapter on the Blau stones. She describes the scene on the reverse of the plaque as follows (p. 17): “Auf der Rückseite des ‘Schabers’ steht eine Figur mit der gleichen Handhaltung, im schraffierten Rock, sie ist jedoch völlig kahlrasiert; ihr zugewandt hocken zwei unbekleidete kahlköpfige Männer, die mit langen Geräten – Stößeln oder Bohrern – hantieren; hinter ihr sitzt ein dritter Handwerker. Dieser Handwerksarbeit kommt bildlich auf beiden Denkmälern eine so große Bedeutung zu, daß sie auch mit der Transaktion, die im Text festgelegt wurde, in Zusammenhang stehen könnte.” In view of zadim as a possible key term in the text, it seems very likely that the workers are indeed using “Bohrer,” that is, drills,6 producing stone vessels or cylinders seals. Comparable representations from the Third Millennium can be found in Egypt (see fig. 4.12).

Fig. 4.12: Stone-cutters using drills on the Blau plaque (?) and on monuments from Ancient Egygpt. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 12); Kayser (1969, 15, fig. 11); Gorelick and Gwinnett (1979, 24); O’Neill (1999, 123, fig. 73).

“DU”/“ŠITA~a3” = S377/GIŠ

The sign transliterated DU by Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting and ŠITA~a3 by CDLI in line 4 of the obelisk is certainly identical with S377 = sign no. 377 in E. Burrows’ list of archaic signs from Ur. As already noted by Burrows (1935, plate 30, no. 377), S377 is attested only as part of the sign combination S377.PA4.NE, which later became GIŠ.GIBIL and GIŠ.NE, read bil3 and bil4, respectively. The most famous occurrence of GIŠ.GIBIL/NE is in early spellings of the name “Gilgamesh,” approximately pronounced (pa)bilga-mes in the time of the archaic texts. On the Blau obelisk, the alleged “DU” or “ŠITA~a3” appears in the vicinity of NE, PA4, and ALAM. The combination of the four signs yields a personal name pa4-bil4-alam, which is also attested in the archaic texts from Ur (see fig. 4.13):

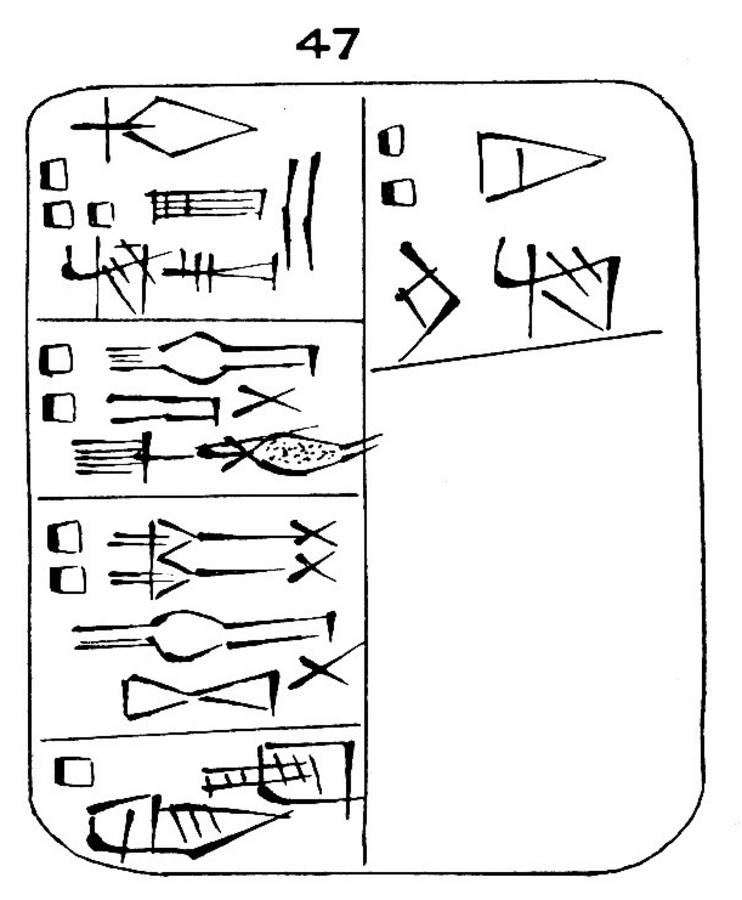

Fig. 4.13: Archaic administrative text from Ur. From Burrows (1935, plate VII).

As can be observed on the same tablet (UET 2 = Burrows 1935, no. 47), the transformation of S377 into GIŠ had already begun by the time of the archaic Ur archives. S377 was already correctly identified and connected with NE by K. Fenzel, who saw here a personal name “pa-bil4-alam-ib-GÍR.” It is indeed very highly probable that we deal here with a personal name. It should comprise, however, as typological parallels suggest, only the signs pa4-bil4-alam (order of signs uncertain). Thus, we find alam-abzu, alam-kurta, lugal-alam, and munus-alam in the archaic texts from Ur. The closest parallels are obviously lugal/munus-alam, in which pa4-bil4 “older relative,” lugal “king,” and munus “women” all designate persons. The identification of pa4-bil4-alam as a personal name leaves us with two remaining signs, IB and ZADIM. If zadim “stonecutter” is meant here, ib must be a specification like “stone-cutter of the ib,” where ib could be the designation of a sanctuary well attested in Early Dynastic inscriptions.

“JN-312”/“|NI~ax1(N57)|” = IL2

My next suggestions concern the last line of the plaque. It seems likely to me that the sign transliterated JN-312 by Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting and |NI~ax1(N57)| by CDLI combined with the SAG next to it is the ancestor of the later sign IL2. It represented the Sumerian noun du(b)si(g) “basket” (> Akkadian tupšikku) as well as two verbs for “carry,” il2 and gur3. These notions would have been symbolized by a burden or a support together with a burden (perhaps a jar) on top of a “head” (SAG). A transitional sign form may be found in line 2' of a literary (?) fragment from Fāra (S 800), which seems to be older than the majority of the Fāra texts (see fig. 4.14).

Fig. 4.14: Archaic form of IL in a fragment from Fāra. From Krebernik, Steible and Yıldız (2015, 378).

“NUNUZ” = ZA

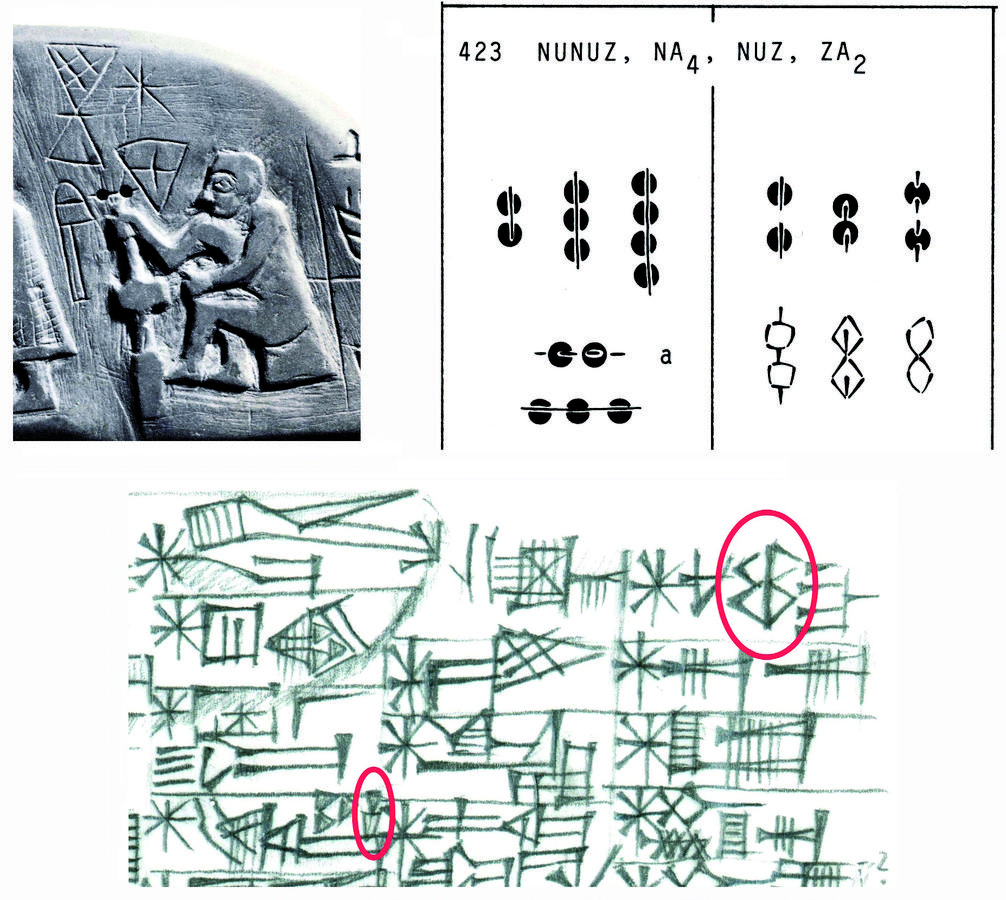

The sign transliterated NUNUZ in both editions should rather be interpreted as ZA. According to the ZATU no. 423, both signs were originally identical: sign forms similar to that of the Blau plaque are registered as NUNUZ, but a value ZA2 is also postulated. In the archaic texts from Ur and in the Fāra texts, however, NUNUZ and ZA are clearly distinguished: ZA consists of circular or half-circular stylus-impressions with vertical wedges inside, whereas NUNUZ consists of two lozanges with vertical wedges inside (see fig. 4.15).

Fig. 4.15: The signs ZA and NUNUZ. From Gelb, Steinkeller, and Whiting (1989–1991, plate 12); Green, Nissen, Damerow, and Englund (1990, 261); MK.

The similarity between the two signs seems to reflect the similarity of the objects originally depicted: two (and originally more) beads on a string (ZA) and two eggs (NUNUZ), respectively. If the Blau stones indeed date to the Early Dynastic period, the distinction described above should be valid, and the sign in question therefore be identified as ZA. It occurs next to ZADIM and it is possible that the two signs are to be connected. If so, ZA could be a phonetic indicator or a specification of ZADIM. Since ZADIM occurs earlier in the text three times without ZA, the first alternative is unlikely, but a meaning like “stonecutter of beads, bead maker” is conceivable.

Structure and Contents

Let us finally look back to the text as a whole and briefly discuss its structure. As already stated above, the obelisk deals with the field, and the plaque with the gifts involved in the transaction.

Obelisk: The field is present in the very beginning of the text in the shape of the sign GANA2 and a number expressing its size. The line contains 6 more signs. Their interpretation is difficult because the arrangement of signs within a line was still free in the period of our text. Thus, one has the choice among a variety of possible alignments and groupings. I have already argued against the combination nin-mug (name of a goddess). Both nin and munus are common elements of Early Dynastic personal names. nin, on the other hand, could by itself refer to a “queen,” and zadim most probably refers to a “stonecutter.” If both interpretations are accepted, the remaining four signs could represent a personal name, munus-u8 “the woman is (like a) ewe,” and a toponym or hydronym, ḪA.RAD (RAD “canal,” ḪA “fish”). Unfortunately, I was not able to find the presumed personal name or close parallels of it in other sources, but the latter assumption can be supported by structural considerations—as in later kudurrus, the location of the field could be specified—and by similar expressions in the following lines: RAD.GI4 and ḪA.UR2.LAK131. Note that each has one sign in common with ḪA.RAD. ELTS considers ḪA.RAD and ḪA.UR2.LAK131 as toponyms and connects them with Urum = Tell ʿUqair (archaic spelling ḪA.RAD.UR2) and Tub/wa (spelled A.ḪA). The last line can easily be related to the “field” of line 1 through the sign APIN, which in later texts expresses apin “plough,” uru4 “to till,” and engar “ploughman.” AB is most probably to be understood as “sanctuary” or perhaps better “temple (household),” a meaning associated later with its value eš3. ELTS translates the term as “agronomos of the temple household” and considers it as the title of the person named in the previous line. This line contains, however, according to my analysis, a personal name, pa4-bil4-alam, together with a title, zadim ib. Therefore, the “agronomos of the temple household” must be another person, referred to only by his function (which is very often the case in Early Dynastic administrative texts). Thus, the obelisk seems to mention three persons connected with the field: (1) one zadim (line 1) probably associated with the nin and furthermore with the following toponyms, (2) a second zadim (line 4) associated with the ib(-sanctuary), and (3) a non-zadim, the “ploughman of the temple (household).”

Plaque: Two sections listing quantified commodities are clearly recognizable (lines 1-5, 7–14/15). As far as the individual items are concerned, I do not want to go into lexical discussions and speculations here but only comment briefly on one of them: ELTS considers the possibility that BA.DAR in line 1 represents a noun borrowed from Akkadian patarru “sharp tool, prod” and spelled ba-da-ra in later Sumerian texts. This is unlikely, not only because the identity of the first sign—IGI or BA—is uncertain, but also because lines 1–2 seem to contain parallel expressions, each composed of IGI/BA and the name of a bird: dara “francoline” and NAM = sim “swallow,” respectively. A similar observation can be made in the two hitherto unexplained lines 4–5, where the common element is EN is combined with ŠA3 and A.

Either section is followed by the name of a zadim (lines 6 and 16). The second section involves, however, a problem which has already been addressed above: Is line 15 indeed a separate line containing a personal name ḫašḫur-lal3, or do lines 14–15 constitute one single line, in which case ḫašḫur lal3 “apple” and “honey” would specify kaš “beer”? Arguments for both possibilities can be adduced, but in my opinion the stronger ones speak in favor of the first possibility. Though I cannot find further evidence for the personal name ḫašḫur-lal3, meaning something like “sweet apple,” it seems not impossible since lal3 is a common element of Early Dynastic personal names. The function or title which one would expect can be easily supplied by referring zadim in line 16 to both preceding names. This interpretation can be supported by the iconography: the three craftsmen depicted on the reverse of the plaque, one of them bigger and more prominent than the two others, would neatly correspond to the zadim gal “chief stone-cutter” of line 6 and the two zadim za “stone-cutters of beads” named in lines 14–15.

If we rightly assume that the two Blau stones document the sale and purchase of a field, and if the sign ZADIM has been identified correctly as a key-term meaning “stone-cutter,” it follows that the sellers as well as the buyers were stone-cutters. The two contracting parties are mentioned on and probably also symbolized by the two differently shaped monuments. Even if the identification of the two parties is uncertain—most probably the sellers are the zadims on the obelisk, and the buyers are the zadims on the plaque—we can state that the transaction implies a guild of “stone-cutters” associated with the “queen” (nin) and with religious institutions (AB, ib). The property transaction obviously involved a ritual (as attested in later periods) which was headed by the dominant male figure depicted on the reliefs who is commonly identified with the En or “priest-king” of Uruk. The confirmation or rejection of the scenario suggested here as well as the further elucidation of the ritual depend, inter alia, on a new look at the iconographic details which I would like to recommend to my archaeological colleagues.

Postscript

After submitting my contribution, I noticed that the craftsmen depicted on the Blau plaque had previously been interpreted, on purely iconographical grounds, as stone-cutters by W. Max Müller in 1915 in an article on “Steinbohrer in Altbabylonien,” Orientalistische Literaturzeitung, 18, 266–268 (not mentioned in Braun-Holzinger (2007)).

References

Boese, Johannes (2010). Die Blau’schen Steine und der ,Priesterfürst‘ im Netzrock. Altorientalische Forschungen 37:208–229.

Braun-Holzinger, E. A. (2007). Das Herrscherbild in Mesopotamien und Elam. Spätes 4. bis frühes 2. Jt. v. Chr. Alter Orient und Altes Testament, 342. Münster: Ugarit Verlag.

Burrows, Eric (1935). Ur Excavations, Texts. II: Archaic Texts. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

CDLI (n.d.). Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. url: http://www.cdli.ucla.edu/.

Damerow, Peter and Robert K. Englund (1989). Bemerkungen zu den vorangehenden Aufsätzen von A. A. Vajman unter Berücksichtigung der 1987 erschienenen Zeichenliste ATU 2. Baghdader Mitteilungen 20:133–138.

Deimel, Anton (1922). Die Inschriften von Fara, I. Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft 40. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

Fenzel, Klaus (1975). Überlegungen zu den „Blau’schen Steinen“: Zur Diskussion über altsumerische Rechtsurkunden. Berlin: Eigenverlag Dr. K. Fenzel.

Gelb, Ignace J., Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert M. Whiting (1989–1991). Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus. Oriental Institute Publications 104. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Gorelick, Leonard and John Gwinnet (1979). Ancient Lapidary: A Study Using Scanning Electron Microscopy. Expedition 22:17–32.

Green, Margaret W., Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, and Robert K. Englund (1990). Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk (ATU 2). Berlin: Gebrüder Mann.

Hrouda, Barthel (1991). Der Alte Orient. Gütersloh: S. Bertelsmann.

Kayser, Hans (1969). Das ägyptische Kunsthandwerk. Braunschweig: Klinkhardt & Biermann.

Krebernik, Manfred (1993–1994). Review of Gelb/Steinkeller/Whiting 1989/1991. Archiv für Orientforschung 40/41:88–91.

Krebernik, Manfred, Horst Steible, and Fatma Yıldız (2015). Prä-Fāra-zeitliche Texte aus Fāra. In: Babel und Bibel 8: Studies in Sumerian Language and Literature. Festschrift Joachim Krecher. Ed. by Natalia V. Koslova, E. Vizirova, and Gabor Zolyomi. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 327–382.

Mallowan, Max E. L. (1961a). Early Mesopotamia and Iran. London: Thames & Hudson.

– (1961b). The Birth of Written History. In: The Dawn of Civilization. Ed. by Stuart Piggott. London: Thames & Hudson, 65–96.

Ménant, M. Joachim (1888). Les fausses antiquités de l’Assyrie & de la Chaldée. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

Nagel, Wolfram, Eva Strommenger, and Christian Eder (2005). Von Gudea bis Hammurapi: Grundzüge der Kunst und Geschichte in Altvorderasien. Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau.

Nissen, Hans J., Peter Damerow, and Robert K. Englund (1993). Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O’Neill, John P. (1999). Egyptian Art at the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Arts.

Seipel, Wilfried (2003). Der Turmbau zu Babel: Ursprung und Vielfalt von Sprache und Schrift. Graz: Skira.

Thureau-Dangin, François (1898). Recherches sur l’Origine de l’Ecriture Cunéiforme. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

Footnotes

Early cuneiform documents are subdivided into “cases” or “boxes” rather than “lines.” In the following, however, I will use the conventional term “line.”

Cuneiform sources are rendered either in transliteration (graphemic level, single cuneiform signs) or in bound transcription (phonemic level). The two levels are distinguished in this article by the different fonts and styles exemplified here.

Mallowan (1961b, 72f; 1961a, 65f), with illustrations.

ZATU + number symbolizes and identifies cuneiform signs (mostly of unknown reading) with reference to the Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk (Green et al. 1990). A similar use is made of LAK + number and S + number, referring to the Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen by A. Deimel (1922), and to the Sign List in Burrows (1935), respectively.

For ancient drills and drilling techniques see, e.g., the articles by Gorelick and Gwinnett listed in the bibliography (with numerous illustrations and bibliography).