Chapter structure

- 5.1 Lingua Sacra Equated

- 5.2 Claiming Lingua Sacra in Vernacular Traditions

- 5.3 Domesticating the Bible and Quran Through the Meta-Language of Ritual: The Theologeme of the Filial Sacrifice in Abrahamic Religions

- 5.4 Onomastica Biblica as Ethnobotanical Taxonomy

- 5.5 Biblical Ancestors as Agents in Magic Spells

- 5.6 Imagining the Voice of God

- 5.7 God’s Speech Depicted

- Appendix

- References

- Footnotes

на майка ми, за чийто рожден ден не можах да си дойда тази година

5.1 Lingua Sacra Equated

The

The empirical data registered during anthropological, ethnographic and folklore

A similar stance towards the Quranic corpus was attested among some Muslim communities—both Sunni and Shia—in the Balkans4 and elsewhere.5 Thus, in the early 1950’s, while describing certain idiosyncratic features of the Alevi

The singer also sung one wise song of Tarikat, in which it was said that man was created from four components: earth, fire, air, and water.8 Four books speak about what is known about air, earth, Şeriat, Tarikat, righteousness and truth. Tarikat is a burning fire, and wealth in material goods was given by Adam to mankind, whereas reasoning was given by Allah. When one goes towards truth, one makes sacrifices. At the end of the song, a question was asked about what is known regarding the destiny of each human being.9

Певецът изпя и една мъдра песен за тарикат, в която се казва, че човек е създаден от четири неща: пръст, огън, въздух и вода. Четири книги отговарят какво знаят за въздуха, земята, за шариаха, за тариката, за правдата и истината. Тарикат е горящ огън, имането—материалните блага били дадени от Адам на човека, съзнанието—от Аллаха. Когато се отива към правдата, дават се жертви. На края в песента се запитва какво се знае за съдбата на всеки човек.10

Тhis kind of sacred vocal music was traditionally performed by either male or female members of the Aliani Kizilbaş community, as there were no gender restrictions imposed upon those singing the “wise chants of Tarikat”;11 significantly, the above information was given by no one else but the local Head of the Village Council [Председател на Селсъвета], Hyusein Merdanov.12 Most remarkably, it was also comrade Merdanov who testified that “these songs are called by our people Quran” [тези песни нашите ги наричат Kуран].13 Obviously, in the above phrase this term did not refer to the Muslim

The academic discourse dominant today is that there are no surviving vernacular parallels to the ancient proto-Biblical oral corpus; yet, at the same time, it is taken for granted that certain literary parabiblical compositions (such as

Then again, the analysis of a parabiblical oral corpus

Thus among Orthodox Russian peasants

| От того колена от Адамова, | From the very knee/loin of Adam himself, |

| От того ребра от Евина, | From the very rib of Eve herself, |

| Пошли христиане православные, | Sprang Orthodox Christians, |

| По всей земли Святорусския.i | Around all the land of Holy Russia.ii |

Tab. 5.1: iSee Danilov (1938, 274).iiSee Badalanova (2008, 183) and Russell (2009, 178).

The motif of Adam and Eve

| Оттого у нас в земле цари пошли | This is how the Tsars of our land sprang |

| От святой главы от Адамовой; | From the holy head of Adam; |

| Оттого зачадились князья-бояры | This is how noble princes came to be |

| От святых мощей от Адамовых; | From the holy relics of Adam; |

| Оттого крестьяны православные | While the Orthodox peasants [sprang] |

| От свята колена от Адамова.i | From the very knee/loin of Adam.ii |

Tab. 5.2: iMochul’skiĭ (1887, (17:1): 178).iiAuthor’s translation.

Tab. 5.2: iMochul’skiĭ (1887, (17:1): 178).iiAuthor’s translation.

Significantly, a strong phonetic similarity exists between the Russian

Then again, a similar—but much more extreme and hostile—axiological model in designating “the Other” is employed by Procopius of Caesarea

The latter case—which is far from unique—not only shows how ethnonyms

A similar phenomenon is observed in medieval European vernaculars; thus the expletive “bugger,” which is conventionally used to denote sodomy, is in fact a derivate from Anglo-Norman bougre, which, in turn, comes from the Latin Bulgarus,26 a name given to the members of the Bulgarian dualistic (Gnostic) heretical movement of the Bogomilism

As far as the actual heresiological term Bogomil is concerned, it is, in fact, an eponym associated with the legendary tenth century leader of the aforementioned Bulgarian dualistic movement who, according to the contemporary historiographical sources, was called Bogomil / Bogumil (Medieval Bulgarian Богоумилъ).28 The latter is a Slavonic calque of the Greek / Byzantine Theophilus (Θεόφιλος), deriving from the lexemes θεός (“God”) and φιλία (“love”). As such, it appears to be a theophoric appellation, the meaning of which may be rendered simply as the “Love of God,” or “Loved by God.” Needless to say, this particular meaning of the (most probably assumed) name of the charismatic heresiarch Bogomil / Bogumil was transparently clear to his contemporaries, regardless of whether adherents or adversaries. It was an ethnohermeneutical

It was exactly this reading of the name of the immanent heresiarch which was targeted by the medieval Bulgarian writer Cosmas the Presbyter

As pointed out above, in the West the term Bogomil was substituted by the ethnonym

5.2 Claiming Lingua Sacra in Vernacular Traditions

The analysis of the vernacular thesaurus employed in parabiblical oral heritage provides fascinating results. Of particular importance is the corpus of the Folk Genesis, as attested among peasant Christian communities in Europe and elsewhere. Those storytelling the Bible consider themselves to be “a chosen people,” while their native tongue is distinguished as the language of Holy Scriptures; accordingly, their native landscapes are identified as the Holy Land.

Indicative in this respect are some folklore counterparts of the Biblical account about the creation of woman,30 as recorded among Bulgarians. Thus, after naming all the animals brought before him, Adam took a nap; it was then, during this slumber that the Matriarch was fashioned by God; the first man called upon her as soon as he woke up. The words he uttered while approaching her were, “Come, come here, as you are dear to my heart!” [Ела! Ела! Че си ми скъпа на сърцето!]; then again, in Bulgarian the articulation/vocalization of the imperative form of the verb “to come”—“ela!” [eлa!]—phonetically resembles the name of the first woman; in the local dialect

A similar rendition of the legend about the origin of the name of the “mother of all living,” Eve, was registered among other Slavonic communities. According to one such an account,32 God conceives the idea of giving the lonely Adam a companion by taking the ninth rib from the sleeping man, forming from it woman and putting her next to him. When Adam awakens, he exclaims: “Lo and behold! What is the meaning of all this? I was one when falling asleep, and now there are two of us!” [Е-во! Што такоя значить? Лех я адин а таперь ужу двоя!]. In the local dialect the expression “Lo and behold” is pronounced as “E-vo!”: hence the name “Eva” (Eve). Having heard Adam’s exclamation, God decides to name the woman after it [Гаспоть и ни пиримяниу названия Адамавый жаны—так и засталась ина Ева].33 As pointed out by Vladimir Dal’ in his Interpretative Dictionary of Vernacular Russian [Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка], “e-va” [е-ва] is a typical Russian vernacular expression used either as an interjection, or as a demonstrative pronoun.34 Obviously, according to the above quoted legend, the name of the first woman is believed to have originated from the exclamation which the Russian-speaking Adam utters when he sees her for the first time.

A similar example of ethnohermeneutical decoding of the name of Eve is attested among the Ukrainians. According to one such anthropogonic legend, man was created from earth, whereas woman was made from the willow tree, which in the narrator’s mother tongue

A similar idea is represented in some Slavonic legends about the origins of the dog. According to these texts, dogs are believed to have sprung from Cain’s dead body—hence the phonetic similarity between their “language” and the name of the Biblical character from whose flesh they originated. While “speaking,” they are believed to be calling his name. Thus the sounds of dog’s barking (rendered by the storytellers as “Kaine! Kaine!”) are perceived as a vocative form of the name of Cain [Каин] (pronounced as “Kain”).36

Another example of deciphering the “language” of animals

Furthermore, even Aetiological legends

Over the many years of my field research I kept encountering the same type of narrative over and over again in different villages. As a rule, the storytellers insisted that the Flood had taken place in their own vicinity; some even showed me the place where Noah’s Ark was believed to have landed.40 (A similar case is represented by legends binding the story of the wife of Lot, who was turned into a pillar of salt within the local landscape). To return to the Flood story, as attested in the Balkans, in some cases the Biblical Patriarch was given a typical local (Bulgarian, Serbian, etc.) name, thus becoming an honorary ancestor of the village in which the Flood story was narrated. In the account of another storyteller, a peasant woman Zonka Ivanova Mikhova (born in 1909 in North-Western Bulgaria), the Biblical legend of Noah and the Flood

And the grapevinehad grapes but they were still green, not yet ripe. He ate from it and said: “No, you can’t eat that!” And when they were ripe, he pressed them and drank wine from them. And he drank and drank, and had more than enough, and got drunk and lay down to sleep. He had taken his clothes off as well. And one of his sons came, and said: “Look! My father is naked!” And the other said: “Forget about him! It’s well deserved—he was so greedy he drank himself to death!” And he woke up and said that he who said that his father should sleep, he will be blessed. Wherever he goes, he will be happy. He who said that his father was naked, he will roam and roam, and never find peace to settle! He will have nothing! [...] And the one who obeyed his father, he was the forefather of the Bulgarians.41

The above quoted oral tale also shows how the Folk Bible

5.3 Domesticating the Bible and Quran Through the Meta-Language of Ritual: The Theologeme of the Filial Sacrifice in Abrahamic Religions

The

Thus in Christian folklore, as registered among the Southern Slavs, the songs of “Abraham’s sacrifice”

Fig. 5.1: Abraham’s sacrifice. Fresco from the Dragalevtsy Monastery of the Dormition of the Mother of God, Bulgaria (1476). Photo FBG.

Fig. 5.2: Abraham’s sacrifice. Painted panel of the iconostasis of the Church of Saint Athanasius in the Village of Gorna Ribnitsa, South-Western Bulgaria (1860). Photo FBG.

Then again, the vernacular Slavonic and Balkan terminology related to the Kurban

Thus, the life of Abraham

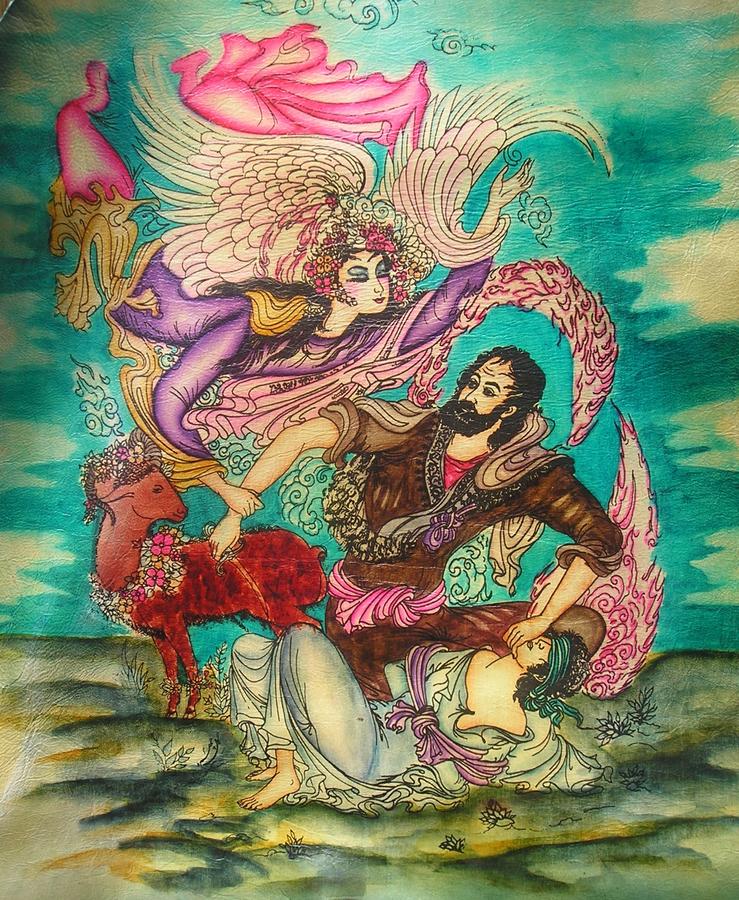

Fig. 5.3: Ibrahim’s Sacrifice. Persian, provenance unknown. Photo FBG.

As for Islamic

As for the functional parameters of folklore counterparts of the Quranic account of the filial sacrifice, they remained constant.58 Whatever way it is narrated, the story of Abraham (whose name now changes to Ibrahim) validates the main custom of Muslim communities—the annual ritual slaying of the lamb or ram at the end of the Ramadan fast, on the feast day traditionally called Kurban-Bayram

It is significant for our line of argument that some peculiar motifs in the filial sacrifice story (but surprisingly absent from the canonical narrative), which feature prominently and systematically in parabiblical Jewish writings from the Hellenistic period, are also attested in medieval Slavonic apocryphal writings and in contemporary Slavonic and Balkan Christian and Muslim folklore. One such detail concerns Isaac’s request to be bound by his father before being slaughtered on the altar as a sacrificial offering to God.

The earliest attestation of this motif can be traced back to the Dead Sea scrolls

| col. i | ||

| 7 | And [Abraham] | |

| 8 | be[lieved] God, and righteousness was reckoned to him. A son was born af[ter] this | |

| 9 | [to Abraha]m, and he named him Isaac. But the prince Ma[s]temah came | |

| 10 | [to G]od, and he lodged a complaint against Abraham about Isaac. [G]od said | |

| 11 | [to Abra]ham, ‘Take your son Isaac, [your] only one, [whom] | |

| 12 | [you lo]ve, and offer him to me as a burnt offering on one of the [hig]h mountains, | |

| 13 | [which I shall point out] to you.’ He aro[se and w]en[t] from the wells up to Mo[unt Moriah]. |

| 14 | [ ] And Ab[raham] raised | |

| col. ii | ||

| 1 | [his ey]es, [and there was a] fire; and he pu[t the wood on his son Isaac, and they went together.] | |

| 2 | Isaac said to Abraham, [his father, ‘Here are the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb] | |

| 3 | for the burnt offering?’ Abraham said to [his son Isaac, ‘God himself will provide the lamb.’] | |

| 4 | Isaac said to his father, ‘B[ind me fast’]i | |

| 5 | Holy angels were standing, weeping over the [altar] | |

| 6 | his sons from the earth. The angels of Mas[temah] | |

| 7 | rejoicing and saying, ‘Now he will perish.’ And [in all this the Prince Mastemah was testing whether] | |

| 8 | he would be found feeble, or whether A[braham] would be found unfaithful [to God. He cried out,] | |

| 9 | ‘Abraham, Abraham!’ And he said, ‘Yes?’ So He said, ‘N[ow I know that] | |

| 10 | he will not be loving.’ The Lord God blessed Is[aac all the days of his life. He became the father of] | |

| 11 | Jacob, and Jacob became the father of Levi, [a third] gene[ration.]ii |

Tab. 5.3: iThis hypothetical restoration of the text (with a reference to the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan) is explained in Fitzmyer (2002, 218); the “plausibility of this reconstruction,” however, is challenged by Kugel who provides arguments against it and offers an alternative reading (Kugel 2006, 86–91, 97). See also VanderKam (1997, 241–261).iiSee Fitzmyer (2002, 216–217). See also the discussion in Fitzmyer (2002, 218–222, 225, 228–229).

Tab. 5.3: iThis hypothetical restoration of the text (with a reference to the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan) is explained in Fitzmyer (2002, 218); the “plausibility of this reconstruction,” however, is challenged by Kugel who provides arguments against it and offers an alternative reading (Kugel 2006, 86–91, 97). See also VanderKam (1997, 241–261).iiSee Fitzmyer (2002, 216–217). See also the discussion in Fitzmyer (2002, 218–222, 225, 228–229).

As shown above, the motif of “Isaac as a willing victim” plays a significant role in the Pseudo-Jubilees

A similar line of argument is observed in some midrashic

“O my father! Bind for me my two hands, and my two feet, so that I do not curse thee; for instance, a word may issue from the mouth because of the violence and dread of death, and I shall be found to have slighted the precept, ‘Honour thy father’ (Ex.20:12.)” He bound his two hands and his two feet, and bound him upon the top of the altar, and he strengthened his two arms and his two knees upon him and put the fire and wood in order, and he stretched forth his hand and took the knife [...]60

A similar scenario is revealed in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan

“Tie me well lest I struggle because of the anguish of my soul, with the result that a blemish will be found in your offering and I will be thrust into the pit of destruction.” The eyes of Abraham were looking at the eyes of Isaac and the eyes of Isaac were looking at the angels on high [...]61

Almost identical wording is employed in Targum Neofiti

And Abraham stretched out his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son Isaac. Isaac answered and said to his father Abraham: “Father, tie me well lest I kick you and your offering be rendered unfit and we be thrust down into the pit of destruction in the world to come.”62

It is rather astonishing that the motif of Isaac’s request to be bound by his father before the sacrifice, first attested in Qumran

5.4 Onomastica Biblica as Ethnobotanical Taxonomy

The

Against witchcraft some herbs may be used, such as wormwood, nettle and the plakun–grass; these, together with “Adam’s head” and “Peter’s cross” may be purchased in [the markets in] the area of the Moskvoretsky Bridge and the Glagol [neighborhood] at a good price.

Против колдунов и ведьм употребляли траву чернобыльник, крапиву и плакун-траву, которая и сейчас в Москве имеется, вместе с Адамовой головою и Петровым крестом у Москворецких ворот и на Глаголе продается за хорошую цену.66

A brief survey of internet sources indicates an abundant corpus of rather curious popular manuals describing the properties of “Adam’s head,” along with the necessary rituals accompanying its proper harvesting and usage. One such source is Andrey Romanovsky’s booklet

practically all the components of magical recipes may be acquired in the shops or in the market; if one cannot find them there, they will be available in specialized shops. One should also remember the internet-shops, in which anything imaginable can be ordered.

Практически все из компонентов магических рецептов можно приобрести в магазине или на рынке, в крайнем случае, в специализированном магазине. Кстати, нельзя сбрасывать со счетов и интернет-магазины, в которых можно заказать все что угодно.68

Incidentally, the first item in his list of recommended herbs is, of course, “Adam’s head,” which is supposed to “guarantee omnipotence and invincibility” [дарующая всемогущество]. The elaborate instructions for both root-cutters and users are likewise presented. These types of online sources could be considered as samples of contemporary urban folklore, which so far has been neglected by those studying popular culture of post-Soviet Russia.

As advised by yet another website,69 an additional “Adamic herb” called “Adam’s root” [Адамов корень] is recommended as a remedy against paralysis, epilepsy, impotence, cardio-vascular and infectious diseases, eye problems, a virtual panacea for all kinds of ailments; the potential buyers are further instructed that it can be purchased online; “the price for 55 milliliters is only 250 RUB.”

Phytonyms

5.5 Biblical Ancestors as Agents in Magic Spells

Then

On the other hand, recent surveys of Russian magic folklore

May in the same way the servant of God (say the name) did not feel in himself, in his white body, hernia, from now until forever, for all ages.

Так же раб божий (имя рек) не слышал бы в себе в белом теле ходячей грыжи, отныне и до века, век по веку веков.81

The concept of the pain-free body of the dead ancestor, who continues to protect his progeny and take care of their health problems, is likewise attested in traditional Russian spells against toothache. As pointed out by Yudin, the role of the “heavenly dentist” may be attributed not only to the forefather Adam, but also to Noah

Then again, a survey of traditional Russian medical incantations points to the distribution of healing specializations among various Biblical prophets, patriarchs and kings; thus Abraham and Elijah (along with the Virgin Mary and the apostle Simon the Zealot) are responsible for a good harvest of curative herbs and other medicinal plants [При собирания целебных трав].90 Those suffering from evil eye invoke the Prophet Elijah

Finally, there are prophets and kings who are believed to be able to deal with all kinds of ailments; thus Enoch annihilates all diseases by simply shooting them,103 and Solomon by subduing them; the latter motif most probably stems from Solomon’s portrayal as master of the demons,104 which is attested in the Babylonian

On the other hand, the scope of protective functions attributed to some Biblical figures goes far beyond healing rituals. Thus the prophet and the wonder-worker Elijah is petitioned in collective litanies and rain-making ceremonies (implicitly referring to the Biblical narrative of his having stopped and/or obtained rain in 3 Kings 17 and 18). He also features in incantations against fire, due to his reputation as someone who may call down blazes from heaven, as in 3 Kings 18: 36–39 (see also Figures 5.4 and 5.5).106

King David

Fig. 5.4: The Holy Prophet Elijah in his fiery chariot ascending to heaven. Miniature from the illuminated Ms copied and illustrated by the Bulgarian priest Puncho (Поп Пунчо). The Ms is kept in the Bulgarian National Library under record № 693 (1796). Publication courtesy of the Bulgarian National Library. Photo FBG.

Fig. 5.5: The Holy Prophet Elijah in his fiery chariot ascending to heaven. Fresco from the open gallery of the Rila Monastery, South-Western Bulgaria (1847). Photo FBG.

As noted by Viktor Zhivov,113 this kind of practices reflect the existence of a certain “Russian jurisprudential dualism” [русский юридический дуализм], which may be regarded as a civic counterpart to religious and cultural dualism. In this kind of context, law courts in general may be perceived as personifications of demonic powers. Thus, in juridical vernacular incantations, magistrates appear to be symbolically equated with diseases or evil spirits;114 accordingly, the antidote against them is similar to that used in healing spells

On the other hand, those embarking on a journey may pray either to Jacob or to Joseph (who was sold by his brothers as a slave and taken away from his homeland); this kind of incantation most probably reflects not only Jacob’s own travels from Canaan to Padan-Aram, after having defrauded his twin brother Esau of his birthright, or Joseph’s forced exile to Egypt, but also, and most importantly, the motif that the journey was safely accomplished. In fact, the incantations associated with “going to a law court” and/or “embarking on a journey” have a rather similar structure; this is also the case with apocryphal tradition. As pointed out by Yatsimirskiĭ in his seminal work, On the History of False Prayers in South-Slavonic Literature, this type of “false prayer”

Last but not least, there are special incantations intended to blunt the weapons of one’s opponents, and in these the name of the Jacob features prominently once more, perhaps because of his successful wrestling with an angel and at the same time averting the anger of his threatening brother Esau when returning to his homeland.

One final point: a survey of Slavonic vernacular

In general, however, the perception of Biblical figures in all aspects of healing and magic

5.6 Imagining the Voice of God

Following the template of Biblical cosmology

[Saint] John said, “From what are thunder and lightning created?”—[Saint] Basil said, “The voice of God is embedded in a fiery chariot and thundering angels are fixed to it.”

І[оаннъ] р[ече]: Отъ чего громъ и молнія сотворена бысть?—В[асилій] р[ече]: Гласъ Господень въ колесницѣ огненной утверженъ и ангела гр(ом)ная приставлена.120

In Slavia orthodoxa (and especially in Russian

5.7 God’s Speech Depicted

Visual counterparts of Holy Scriptures represent yet another code of transmission

For to adore a picture is one thing, but to learn through the story of a picture what is to be adored is another. For what writing presents to readers, this a picture presents to the unlearned who behold, since in it even the ignorant see what they ought to follow; in it the illiterate read. Hence, and chiefly to the nations, a picture is instead of reading.122

Indeed, the rustic Homo legens lacked scribal eloquence yet could “read” the “sentences” of icon-painting, not envisaged as an act based upon the knowledge of letters. Without being familiar with the alphabet, believers were able to “read” the Bible

Fig. 5.6: Jesus asleep in the Balkan Mountains. Fresco from the Church of The Holy Prophet Elijah

Appendix

The text below follows the following conventions: [ ] indicate conjectural additions in the English translation.

Part 1: Biblical Onomasticon in Oral Incantations, Charms and Spells

Text № 1: Love-attraction spell (charm to dry one up; erotic enchantment)

To be recited over food or drink which is to be given [secretly] to the woman/maiden to be behexed, or over her footprints.

O Lord God, Christ—bless!

I, the servant of God, So-and-so, after my having blessed myself, will set off, and having crossed myself, I will go from the dwelling through the doors, and then through the courtyards and gates, into the pure fields. In the pure fields, in the green bushes, in the seashore there is a cave; in this cave, an elderly woman is sitting on a golden chair between three gates. I, the servant of God, So-and-so, pray to her:

“O you elderly, senior woman, you are endorsed by the Lord and the Most Holy Virgin, to enlighten me, the servant of God, So-and-so, about Adam’s Covenant; put into the desired heart of the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, the love of Eve towards me, the servant of God, So-and-so.”

And then the old senior woman, merciful, sweet-hearted, the gold-footed one,123 is dropping the silk yarn and silver spindle and begins to pray to Christ, Heavenly King, and to the Virgin

As the white spring is boiling under the earth ceaselessly in the Summer, so may the heart and soul of [the female] God’s servant, So-and-so, boil and burn after me, the servant of God, So-and-so.

As no man can live without bread, without salt, without garments, without sustenance, so in the same way may the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, not be able to live without me, the servant of God, So-and-so.

As it is hard for fish to live on dry banks without cold water, so may it be for the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, without me, the servant of God, So-and-so.

As it is hard for an infant to live without his mother and for the mother without her child, may it be equally hard for the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, to live without me, the servant of God, So-and-so.

As bulls jump on the cow or as the cow raises her head on the Feast Day of St. Peter and curls her tail, so may it be in the same way that the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, run and search for me, the servant of God, So-and-so, without fear of God or shame of people. May she kiss me in the mouth, embracing me with her arms and make love.

As hops are twisting around the stick according to the sun, so in the same way may the [female] servant of God, So-and so, twist around me, the servant of God, So-and-so.

As the morning dew blossoms, longing for the red sun to come from the high mountains, may also the [female] servant of God, So-and-so, in the same way long for me, the servant of God, So-and-so, every day and every hour, now and always, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Приворотный заговор (присушка, любжа)

Наговаривается на пищу или питье, которые дают привораживаемой, или на след ее.

Господи Боже, благослови Христос!

Стaну я, раб божий (имя рек) благословясь, пойду перекрестясь, из избы дверьми, со двора в ворота, в чистое поле. В чистом поле, в зеленых кустах, в поморье стоит вертеп; в том вертепе сидит матерая жена на золотом стуле между трeх дверей. Молюся я, раб Божий (имя рек) до ней:

“Ты старая матерая жена, тебе дано от Господа и от Пресвятыя Богородицы ведати меня раба Божия (имя рек) Адамов закон, Еввину любовь, вложи желанное сердце рабе Божией (имя рек) по мне, по рабе Божием (имя рек).”

И тут старая матерая жена милостивая, милосердная, золота ступа, покидает шелковый кужелек, веретенце серебрянное, молится Христу Царю Небесному, Богородице, Матери Царице, вкладывает желанное сердце рабе Божией (имя рек).

Как кипит под землею летом беспрестанно белой ключь, так бы кипело, горело сердце и душа у рабы Божией (имя рек) по мне, по рабе Божием (имя рек).

Как всякой человек не может жить без хлеба, без соли, без платья, без ежи, так бы не можно жить рабе Божией (имя рек) без меня, раба Божия (имя рек).

Коль тошно рыбе жить на сухом берегу, без воды студенныя, так бы тошно было рабе Божией (имя рек) без меня, раба Божия (имя рек).

Коль тошно младенцу без матери своей, а матери без дитяти, толь тошно рабе Божией (имя рек) без меня, раба Божия (имя рек).

Как быки скачут на корову, или как корова в Петровки голову закинет, хвост залупя, так бы раба Божия (имя рек) бегала и искала меня, раба Божия (имя рек), Бога бы не боялась, людей бы не стыдилась, во уста бы целовала, руками обнимала, блуд сотворила.

И как хмель вьется около кола по солнцу, так бы вилась, обнималась около меня, раба Божия (имя рек).

Как цвела утренная роса, дожидаясь краснова солнца из-за гор из-за высоких, так бы дожидалась раба Божия (имя рек) меня, раба Божия (имя рек), на всякий день и на всякий час, всегда, ныне и присно и во веки веков, аминь.124

Text № 2: [Spell] for hernia (“white” hernia, or “collar” / “harness”)

To be recited three times; each time after the recitation [the healer] should spit three times.

Having blessed myself, I, the servant of God, will set off, and having made the sign of a cross, will go from the dwelling through the door, and from the courtyard through the gates, to the pure field, via the road along the blue sea.

In the blue sea, there is a holy island of God. On this holy island of God is a holy Church of God. In this holy Church of God there is the Lord’s throne. On this throne of the Lord’s sits the Holy Martyr of Christ Antipas

[Hereby I pray:] “Please heal the suffering and [illness of] tooth pain, and ‘white’ hernia.” And then the Most Holy Martyr of Christ Antipas said, “In this Church of God is Adam’s corpse. Adam’s corpse does not hear the chiming of the bells or church-singing; nor does this, his white corpse, sense ‘walking’ hernia.”

The dead corpse of Adam answers, “I don’t hear the chiming of the bells or church-singing, neither do I sense the ‘walking’ hernia in my white body, either in my nape, or in my sinews, or in my belly, or in my joints, or in my bones, or under my skin, or in my ears, in my eyes, or in my teeth.” So in the same way may the servant of God, So-and-so, not sense in his white body the ‘walking’ hernia, now and forever and to the ages of ages. Amen.

От грыжи: белой грыжи или хомута

Произносится трижды и за каждым разом трижды сплевывается

Стану я, раб Божий, благословясь, пойду, перекрестясь из избы дверьми, из двора воротами, во чистом поле путем дорогою, по край синя моря.

В синем море есть святой Божий остров; на святом Божьем острове святая Божья церковь; в той святой Божьей церкви есть престол Господень, на том престоле Господне есть священномученик Христов Антипа, исцелитель зубной, и безсребренники Христовы Козьма и Дамиан.

“Исцелите скорбь и болезнь зубную и грыжу белую.” И речет священномученик Христов Антипа: “Есть в той Божьей Церкви Адамово тело, не слышит Адамово тело звону колокольнева, пения церковнаго, в белом теле ходячей грыжи.”

И отвещает мертвое тело Адамово: “Я не слышу звона колокольнева, пенья церковнаго, в белом теле ходячей грыжи, тильной, жильной, пуповой, суставной, становой, подкожной, ушной, глазной, зубной.” Так же раб Божий (имя рек) не слышал бы в себе в белом теле ходячей грыжи, отныне и до века, век по веку веков. Аминь.127

Fig. 5.7: The twin brother-physician-saints Cosmas and Damian

Text № 3: [Spell] against toothache

I, the Servant of God, So-and-so, having blessed myself, shall set off and, having made the sign of a cross, shall exit from the dwelling through the doors and from the courtyard through the gates. I will go out to the wide street and will look and stare at the bright new moon.

In this new moon are two brothers, Kavel’,128 and Avel’.129 Just like they don’t feel pain and stinging in their teeth, so may my teeth, of the servant of God, So-and-so, feel neither pain nor stinging.

От зубной боли

Стану я, раб Божий (имя рек) благословясь, выйду перекрестясь, из избы дверьми, из двора воротами. Выйду я на широкую улицу, посмотрю и погляжу на млад светел месяц.

В том младу месяцу два брата родные: Кавель да Авель. Как у них зубы не болят и не щипят, так бы у меня, раба Божия (имя рек), не болели и не щипели.130

Text № 4: [To be recited] when collecting healing herbs

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,131 amen. O Lord and the Mother of God, the Most Holy Virgin Theotokos

The Holy righteous Father Abraham was ploughing the fields, Simon the Zealot [see Figure 5.8]132 was sowing it. [The Holy Prophet] Elijah was watering it. And the Lord was helping. The sky is father while the earth is mother. Please O Lord, bless this herb, to be collected for all kinds of benefits, for all Orthodox Christians. Amen, amen, amen.

When you go to collect these herbs, you must make six prostrations at home and six prostrations in front of the herb.

При собирания целебных трав

Во имя Отца и Сына и Святаго Духа, аминь. Благослови, Господи, Мать Божия, Пресвятая Дева Богородица и святой отец праведный Абрам, я пришел к вам испросить у вас дозволение мне трав сорвать на всякую пользу и от всякой болезни всем православным христианам.

Святой праведный отец Абрам все поле орал, Симеон Зилот садил, Илья поливал, Господь помогал. Небо—отец, а земля—мать. Благослови, Господи, эту траву рвать на всякую пользу всем православным христианам. Аминь (трижды).

Когда идешь траву рвать, нужно сделать шесть поклонов дома и шесть при самой траве.133

Fig. 5.8: Simon the Zealot (Zelotes). Fresco from the Church of St. George in the city of Kyustendil, South-Western Bulgaria (1878–1882). Photo FBG.

Text № 5: [To be recited] while searching for treasure

On

I will bow before the most wise King, having armed myself with God’s word, and with this book will I find my way to treasure hidden in the earth, and with God’s blessing I will go excavating. Grant me—So-and-so—O Lord, to be rid of evil adversaries and to extract gold from the earth for good deeds, to please little orphans, to build God’s temples, to distribute [it] among poor brethren, and for me, So-and-so, for honest business and trade.

При отыскивании кладов

На семи горах на Сионских стоит великий столб каменный; на тем столбе каменном лежит книга запечатана, железным замком заперта, золотым ключем замкнута. На семи горах на Сионских, на столб тот каменный положил книгу запечатану, железным замком заперту, золотыим ключем замкнуту сам премудрый царь Соломон.

Я премудрому царю поклонюся, Божиим словом воорожуся, в книге той о поклажах земных справляюся, с благословением на рытву отправлюся. Подаждь, Боже, мне (имя рек) приставников злых от поклажи отогнати, злата из земли на добрыя дела взяти, сиротам малым на утешение, Божиих храмов на построение, всей нищей братии на разделение, а мне (имя рек) на честну торговлю купецкую.134

Text № 6: [To be recited] when one goes to those in power or to pacify judges

I, the servant of God, will set off towards judges and officials; may their tongue be like an ox’s, their heart be like King David’s,

As a dead person lies in the damp earth without moving his legs, without speaking with this tongue, and without causing evil with his heart, may, in the same way, judges, officials, enemies and foes not speak with their tongues, may they not create trouble with their hearts, may their legs not move, may their hands not rise, may their mouths not open, may instead their blood coagulate, may their eyes blur and be covered with darkness, and may their heads fall off their shoulders.

На подход ко властям или на умилостивление судей

Пойду я, раб Божий, к судьям и начальникам; будь их язык воловий, сердце царя Давида, разсудит нас царь Соломон, Спасова рука.

Как мертвый человек в сырой земле лежит, ногами не движет, языком не говорит, сердцем зла не творит,—так бы судьи, начальники, враги и супостаты языком не говорили, сердцем зла не творили, ноги бы их не подвигалися, руки не подымалися, уста бы не отверзалися, а кровью бы они запекалися, очи бы у них помутилися, темнотою покрылися, с плеч буйна голова свалилася.135

Part 2: Aqedah in folklore tradition

Text № 1: The young fellow Abraham

Wringing his icy hands,

Shedding tears like rain,

And praying to God:

You have given me everything, God,

There is only one thing you haven’t given me—

A male offspring from my heart,

To walk around the courtyard,

To go then to the field,

To go to the field and plough it,

To fetch a cartful of firewood,

Of firewood, and of flour!

An offspring from my heart,

To walk around the courtyard,

To say ‘Mother!,’ and ‘Father!,’

To go then to the field,

To fetch a cartful of firewood,

Of firewood, and of flour!

I vow to slaughter him as a kurban

To the Lord God and to Saint Georgy [George]!”

And they had an offspring from the heart,

And christened him, and named him after Saint Georgy.

Georgy grew, and grew up,

And became a fifteen-year old.

To the field, to plough it,

To fetch a cartful of firewood,

Of firewood and of flour.

When he came back home,

Baking them and weeping.

His father was whetting knives,

Whetting them and weeping.

Georgy said to his mother:

Why are you baking white loaves,

Baking them, mother, and weeping?

Why is father whetting knives,

Whetting them and weeping?

Everybody is joyful,

Why are you so woebegone?”

His mother said to Georgy:

“Don’t ask me Georgy, don’t ask me,

Georgy approached his father

And said to him, asking him:

“Father, my dearest father!

Why are you whetting those knives,

Instead of whetting them and singing?

Why is mother baking loaves,

Baking them and weeping,

Instead of baking and singing?

Everybody is joyful,

And why are you so woebegone?”

“Georgy, my one and only!

How could I whet them and sing,

To slaughter you as a kurban

To Our Lord, to Saint Georgy?”

“Father, my dearest father,

Tie my hands securely,

Lest I could reach anything with my hands,

Lest I could move my legs!”

His father tied his hands,

His hands, as well as his legs,

God descended from Heaven,

God—Saint Georgy himself,

And He held out his hand

And said to him:

A man is not to be slaughtered

As a kurban

A lamb is to be slaughtered instead!”

The father untied his child’s hands,

And went and caught the best ram,

The ram with nine bells,

And slaughtered him as a kurban sacrifice,

And his kith and kin got together,

That is why the feast day of Saint

Mлад Аврам

И кърши ръки като лед

И рони сълзи като дъжд,

Па се на Бога молеше:

Всичко ми, Боже, отдаде,

Само ми едно не даде,

От сърце мъжка рожбица,

По двори да ми походи,

Че на нива да иде,

На нива оран да оре,

Кола дърва да докара,

Кола дърва и кола брашно!

От сърце рожба да видя,

По двори да ми походи,

‘Мамо!’ и ‘Татко!’ да рече,

На нивата да отиде,

Кола дърва да докара,

Кола дърва и кола брашно!

Курбан ще да го заколя,

На Бога, на свети Георги!”

От сърце рожба родиха,

На свети Гьорги кръстиха.

Расъл ми Георги, порасъл,

По на петнайсе години.

На нива оран да оре,

Кола дърва да докара,

Кола дърва и кола брашно.

Кога си у дома дойде,

Хем ги пече, хем плаче.

Тейко му остри ножове,

Хем остри, тейно, хем плаче.

Георги си майци думаше:

Що печеш бели лябове,

Хем ги печеш, мале, хем плачеш?

Що тейно остри ножове?

Ем остри тейно, ем плаче?

Сичките ора—радостни,

Пък вие жалби жалите?”

Мама си Георги продума:

“Немой ме пита, Георги ле,

Георги при тейно отиде

И си на тейно продума:

“Тейне ле, милинкин тейне!

Що остриш тия ножове,

Та ги не остриш да пяеш?

Що мама пече лябове,

Ем ги пече, ем плаче,

Та ги не пече да пяе?

Сичките хора—радостни,

Пък вие жалби жалите?”

“Георги, един на татко!

Как да ги остря и пяя,

Курбан да си те заколи

На Бога, на свети Георги!”

“Тейне ле, милинкин тейне,

Хубаво ми вързи ръките,

Със ръки да не пофана,

Със ноги да не помръдна!”

Тяйно му вързал ръките,

Ръките, още ногите,

Спусна се Господ от небо,

Господ—сам си свети Георги

И му ръката пофана,

И му е дума продумал:

Човек се курбан не коли

На Бога, на свети Георги,

Ами се коли агънце!”

Тейно му ръки отвърза,

Па фанал най баш овена,

Овена с девет звънеца,

Та си го курбан заколил,

Че си е родата посъбрал,

Затуй се тачи Гергьовден! Затуй се коли агънце—курбан на Бога, за здраве и берекет.136

Abbreviations

| AEH | Acta Ethnographica Hungarica. Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (Budapest), Akademiai Kiado, Vol. 1–, 1950 –. |

| BF | Български фолклор. Институт за фолклор при БАН, София, Кн.1–, 1975–. |

| Le Muséon | Le Muséon: Revue d’Études Orientales. Louvain-la-Neuve, T. 1–, 1881–. |

| SbNU | Сборникъ за народни умотворения, наука и книжнина, Кн. 1–27, 1889–1913; Сборник за народни умотворения и народопис, Кн. 28 –, 1914–. |

| SMS | Studia mythologica Slavica. The Institute of Slovenian Ethnology at ZRC SAZU, Ljubljana, and the Department of Linguistics of the University in Pisa, T. 1–, 1998– ; from 1999 onwards it is published in cooperation with the University of Udine. |

References

Čajkanović, V. [Чаjкановић, В.] and V. Đurić [В. Ђурић] (1985). Речник српских народних веровања о биљкама. Рукопис приредио и допунио Воjислав Ђурић. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга, Српска академиjа наука и уметности.

Adler, W. (2013). Palaea Historica (“The Old Testament History”): A New Translation and Introduction. In: Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Ed. by R. Bauckham, J. Davila, and Al. Panayotov. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 585–672.

– (October 1986–1987). Abraham and the Burning of the Temple of Idols: Jubilees’ Tradition in Christian Chronography. The Jewish Quarterly Review (New Series) 77(2/3):95–117.

Andersen, Ø. (1991). Oral Tradition. In: Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Ed. by H. Wansbrough. Journal for the Study of the New Testament. Supplement Series 64. Sheffield: Academic Press (JSOT Press), 17–58.

Andreychin, L. [Андрейчин, Л.] et al. (1963). Български тълковен речник София: Държавно издателство Наука и изкуство

Aune, D. (1991). Prolegomena to the Study of Oral Tradition in the Hellenistic World. In: Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Ed. by H. Wansbrough. Sheffield: Academic Press (JSOT Press), 59–106.

Badalanova, F. (1993). Фолклорен еротикон Том 1. София: Род

– (1994). Biblia Folklorica. BF 20(1):5–21.

– (2002a). Beneath, Behind and Beyond the Bible: Back to the Oral Tradition (The Theologeme of Abraham’s Sacrifice in Bulgarian Folklore). In: Фолклор, традиции, култура (Сборник в чест на Стефана Стойкова) ed. by Стоянка Бояджиева, Доротея Добрева and Светла Петкова. София: Академично издателство Професор Марин Дринов, 47–67.

– (2002b). Folk Religion in the Balkans and the Quranic Account of Abraham. The Slavic and East European Folklore Association Journal 7(1):22–73.

– (2001). Interpreting the Bible and the Koran in the Bulgarian Oral Tradition: the Saga of Abraham in Performance. In: Religious Quest and National Identity in the Balkans. Ed. by C. Hawkesworth, M. Heppell, and H. Norris. London and New York: Palgrave, 37–56.

– (1997–1998). Экскурсы в славянскую фольклорную Библию: Жертва Каина. (Статья первая) Annali Dell’ Instituto Universitario Orientate di Napoli: Slavistica 5:11–32.

– (2003). The Word of God, by Word of Mouth: Byelorussian Folklore Versions of the Book of Genesis. New Zealand Slavonic Journal 37:1–22.

– (2008). The Bible in the Making: Slavonic Creation Stories. In: Imagining Creation. Ed. by Markham Geller et al. Leiden: Brill, 161–365.

Badalanova Geller, F. (2008). Qur’ān in Vernacular: Folk Islam in the Balkans. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Preprint 357.

– (2010). Gynesis in Genesis. In: Forma Formans: Studi in onore di Boris Uspenskij, Vol. 1. Ed. by S. Bertolissi and R. Salvatore. Naples: M. D’Auria Editore (Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale,” Dipartimento di Studi dell’Europa Orientale), 17–48.

– (2015). Between Demonology and Hagiology: Slavonic Rendering of Semitic Magical Historiola of the Child-Stealing Witch. In: In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia. Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures. Ed. by J. Cale Johnson. Berlin: De Gruyter, 177–206.

Bartmiński, J. and S. Niebrzegowska (1996). Słownik stereotyp ów i symboli ludowych. Tom 1. Kosmos: Niebo, światła niebieskie, ogień, kamienie. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersitetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

Bauckham, R. (2006). Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Bezsonov, P. [Безсоновъ, П.] (1861). Калѣки перехожiе: Сборникъ стиховъ и изслѣдование П. Безсонова. Часть І. Вып. 1, 2, 3. Москва: Въ Типографии А. Семена

– (1864). Калѣки перехожiе: Сборникъ стиховъ и изслѣдование П. Безсонова. Вып. 6 (Стихи былевые: библейскiе, старшiе и младшiе). Москва: Въ типографии лазар. инст. вост. языков

Birge, J. (1937). The Bektashi Order of Dervishes. London: Luzac & Co.

Bonchev, A. [Бончев, A.] (2002). Речник на църковнославянския език T. 1–2. София: Народна библиотека Кирил и Методий

Bowen, J. R. (September 1992). Elaborating Scriptures: Cain and Abel in Gayo Society. Man (New Series) 27(3):495–516.

Bozhilov, I. [Божилов, Ив.], Totomanova, A. [Тотоманова, A.], and Biliarski, I. [Билярски, Ив.] (2012). Борилов синодник. Издание и превод София: ПАМ

Brewer, D. (1979). The Gospels and the Laws of Folktale: A Centenary Lecture, 14 June 1978. Folklore 90(1):37–52.

Bushkevich, S. P. [Бушкевич, С. П.] (2002). Ветхозаветные сюжеты в народной культуре Украинских Карпат Живая Старина 3:10–12.

Calder, N. (1988). From Midrash to Scripture: The Sacrifice of Abraham in Early Islamic Tradition. Le Mus éon: Revue d’Études Orientales (The Muséon: Journal of Oriental Studies) 101(3–4):375–402.

Chasovnikova, A. V. [Часовникова, А. В.] (2003). Христианские образы растительного мира в народной культуре. Петров крест. Адамова голова. Святая верба Москва: Индрик

Crone, P. (2012). The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran: Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dähnhardt, O. (1907). Natursagen. Band 1: Sagen zum alten Testament. Leipzig-Berlin: B. G. Teubner.

– (1909). Natursagen. Band 2: Sagen zum neuen Testament. Leipzig-Berlin: B. G. Teubner.

Dal’, V. [Даль, В.] (1880–1882). Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка Владимира Даля. Второе издание Том 1 (А—З), 1880; Том 2 (И—О), 1881; Том 3 (П), 1882; Том 4 (Р—Ѵ), 1882. Санкт Петербург / Москва: Издание книгопродавца-типографа М. О. Вольфа

Danilov, K. [Данилов, К.] (1938). Древние российские стихотворения, собранные Киршею Даниловым Москва Государственное издательство Художественная литература

Davidov, A. [Давидов, А.] (1976). Речник-Индекс на Презвитер Козма. София: Издателство на Българската академия на науките

Delaney, C. (1991). The Seed and the Soil: Gender and Cosmology in Turkish Village Society. Berkeley / Los Angeles / London: University of California Press.

Detelić, M. (2001). Saint Sisinnius in the Twilight Zone of Oral Literature. SMS 4: 225–240.

Dimitrova-Marinova, D. [Димитрова-Маринова, Д.] (1998). Богомильская космогония в древнеславянской литературной традиции In: От Бытия к Исходу. Отражение библейских сюжетов в славянской и еврейской народной культуре. Сборник статей Ed. by В. Я. Петрухин Москва: Центр научных работников и преподавателей иудаики в вузах “СЭФЕР,” Международный Центр университетского преподавания еврейской цивилизации (Еврейский Университет, Иерусалим), Институт славяноведения Российской Академии наук, 38–57.

Dobrovol’skiĭ, V. [Добровольский, В.] (1891). Смоленский Этнографический сборник: Ч. 1. (Записки императорского Русского географического общества по отделению этнографии) Москва / Санкт Петербург: Типография А. Васильева / Типография Худекова.

Dressler, M. (2003). Turkish Alevi Poetry in the Twentieth Century: The Fusion of Political and Religious Identities. Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics (Special Issue: Literature and the Sacred) 23:109–154.

– (2013). Writing Religion: The Making of Turkish Alevi Islam. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Dubrovina, S. Yu. [Дубровина, С. Ю.] (2002). Народные пересказы Ветхого Завета на Тамбовщине Живая Старина 3:2–4.

Dundes, A. (1999). Holy Writ as Oral Lit: the Bible as Folklore. Lanham (Maryland): Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

– (2003). Fables of the Ancient: Folklore in the Qur’an. Lanham, MD / Boulder / New York / Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Elman, Y. and I. Gershoni, eds. (2000). Transmitting Jewish Traditions: Orality, Textuality and Cultural Diffusion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Faraone, C. A. (1999). Ancient Greek Love Magic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fasmer, M. [Фасмер, М.] (1986–1987). Этимологический словарь русского языка T. 1–4. Москва: Прогресс

Fedotov, G. P. [Федотов, Г. П.] (1991). Стихи духовные (Русская народная вера по духовным стихам) Вступительная статья Н. И. Толстого; послесл. С. Е. Никитиной; подготовка текста и коммент. А. Л. Топоркова. Москва: Прогресс / Гнозис.

Finkel, I. (2014). The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Firestone, R. (1989). Abraham’s Son as the Intended Sacrifice (al-Dabih, Qur’an 37: 99–113): Issues in Qur’anic Exegesis. Journal of Semitic Studies 34:95–131.

– (2001). Abraham. In: Encyclopaedia of the Qur’ān, Vol. 1 (A-E). Ed. by J. Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, 5–11.

Fitzmyer, J. A. (2002). The Sacrifice of Isaac in Qumran Literature. Biblica 83(2): 211–229.

Flusser, D. (1971). Palaea Historica: An Unknown Source of Biblical Legends. In: Scripta Hierosolymitana, Vol. 22: Studies in Aggadah and Folk-Literature. Ed. by J. Heinemann and D. Noy. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, the Hebrew University, 48–79.

Gaster, M. (1887). Greeko-Slavonic Ilchester Lectures on Greeko-Slavonic Literature and Its Relation to the Folk-Lore During the Middle Ages. With Two Appendices and Plates. London: Trübner & Co.

– (1900). Two Thousand Years of the Child-Stealing Witch. Folklore 11(2):129–162.

– (1915). Rumanian Bird and Beast Stories (Rendered into English). London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

Geller, M. (2011). The Faceless Udug-demon. Studi e Materiali de Storia delle Religioni 77(2):333–341.

Georgiev, V. et al. [Георгиев, В. et al.] (1971). Български етимологичен речник Том 1 (А–З). София: Издателство на Българската академия на науките

Georgieva, I. [Георгиева, Ив.], ed. (1991). Българските алиани. Сборник етнографски материали София: Университетско издателство Св. Климент Охридски

Gerov, N. [Геров, Н.] (1895). Рѣчникъ на Блъгарскый языкъ съ тлъкувание рѣчи-ты на блъгарскы и на русскы. Събралъ, нарядилъ и на свѣтъ изважда Найденъ Геровъ. Ч. 1: А—Д Пловдивъ Дружествена печатница Съгласие

– (1897). Рѣчникъ на Блъгарскый языкъ съ тлъкувание рѣчи-ты на блъгарскы и на русскы. Събралъ, нарядилъ и на свѣтъ изважда Найденъ Геровъ. Ч. 2: Е—К Пловдивъ Дружествена печатница Съгласие

– (1899). Рѣчникъ на Блъгарскый языкъ съ тлъкувание рѣчи-ты на блъгарскы и на русскы. Събралъ, нарядилъ и на свѣтъ изважда Найденъ Геровъ. Ч. 3: Л—О Пловдивъ Дружествена печатница Съгласие

– (1904). Рѣчникъ на Блъгарскый языкъ съ тлъкувание рѣчи-ты на блъгарскы и на русскы. Събралъ и изтлъкувалъ Найденъ Геровъ. Ч. 5: Р — Я ed. by Теодоръ Панчевъ. Пловдивъ: Дружествена печатница Съгласие

Gippius, A. A. [Гиппиус, A. A.] (2005). Сисиниева легенда в новгородской берестяной грамоте In: Заговорный текст: генезис и структура ed. by Л. Г. Невская, Т. Н. Свешникова, and В. Н. Топоров Москва: Индрик, 136–142.

Grafton, A. and M. Williams (2006). Christianity and the Transformation of the Book. Cambridge and London: Belknap and Harvard University Press.

Gramatikova, N. [Граматикова, Н.] (2011). Неортодоксалният ислям в българските земи. Минало и съвременност София: Гутенберг

Hasan-Rokem, G. (2009). Did Rabbinic Culture Conceive of the Category of Folk Narrative? European Journal of Jewish Studies 3(1):19–55.

Hastings, J., ed. (1898). A Dictionary of the Bible, Dealing with its Language, Literature, and Contents, Including the Biblical Theology. New York / Edinburgh: C. Scribner’s Sons / T&T Clark.

Hrinchenko, B. [Гринченко, Б.] (1927). Словник української мови Том 1 (А-Г). Київ: Горно

Ippolitova, A. B. [Ипполитова, А. Б.] (2002a). Лицевой травник конца18 в. In: Отреченное чтение в России XVII—XVIII веков. Ed. by А. Л. Топорков and A. A. Турилов Москва: Индрик, 441–464.

– (2002b). Травник начала 18 в. In: Отреченное чтение в России XVII—XVIII веков. Ed. by А. Л. Топорков and A. A. Турилов Москва: Индрик, 420–440.

Istrin, V. M. [Истрин, В. М.] (1898). Замечания о Составе Толковой Палеи (5–6). Известия Отделения Русского языка и словесности Императорской Академии Наук 3(2):472–531.

Ivanov, V. V. [Иванов, В. В.] and V. N. Toporov [В. Н. Топоров] (2000). О древних славянских этнонимах (Основные проблемы и перспективы) In: Из истории русской культуры. Том 1 (Древняя Русь). Москва: Языки русской культуры, 413–440.

Ivanov, Y. [Иванов, Й.] (1925). Богомилски книги и легенди София: Придворна печатница (Издава се от фонда Д. П. Кудоглу)

Jong, F. de (1989). The Iconography of Bektashiism. Manuscripts of the Middle East 4:7–29.

– (1993). Problems Concerning the Origins of the Qizilbāș in Bulgaria: Remnants of the Ṣafaviyya? In: Convegno sul tema la Shi‘a nell’Impero Ottomano (Roma, 15 aprile 1991). Rome: Accademia Nazionale Dei Lincei, Fondazione Leone Caetani, 203–215.

Kawashima, R. S. (2004). Biblical Narrative and the Death of the Rhapsode. Indiana Studies in Biblical Literature. Supplement Series 62. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kelber, W. (1983). The Oral and the Written Gospel: The Hermeneutics of Speaking and Writing in the Synoptic Tradition, Mark, Paul and Q. Philadelphia: Indiana University Press.

Kessler, E. (2004). Bound by the Bible: Jews, Christians and the Sacrifice of Isaac. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirkpatrick, P. (1988). The Old Testament and Folklore Study. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

Kiselkov, V. [Киселков, В.] (1942 [1921]). Презвитер Козма и неговата беседа против богомилите Карнобат: Печатница на Д. Ангелов и Ж. Танев (1st Edition). София: Хемус (2nd Edition).

Klyaus, V. L. [Кляус, В. Л.] (1997). Указатель сюжетов и сюжетных ситуаций заговорных текстов восточных и южных славян Москва: Наследие

Kugel, J. (2006). Exegetical Notes on 4Q225 Pseudo-Jubilees. Dead Sea Discoveries 13(1):73–98.

Lincoln, B. (1986). Myth, Cosmos, Society: Indo-European Themes of Creation and Destruction. Cambridge, MA and London, UK: Harvard University Press.

Lozanova, G. [Лозанова, Г.] (2000). Иса и краят на света (каямета) в разказите и светогледа на българските мюсюлмани BF 26(2):63–71.

– (2002). Знамения и неподражаеми чудеса в мюсюлманските разкази за пророци. BF 28(2):36–52.

– (2003). Индивидуалното спасение в разказите за Нух Пейгамбер и Потопа BF 29(2/3):17–27, 206.

– (2006). Пастирски мотиви в разказите за Пророк Муса BF 32(2):19–40, 160.

Manns, F. (1995). The Binding of Isaac in Jewish Liturgy. In: Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Analecta 41. The Sacrifice of Isaac in the Three Monotheistic Religions. (Proceedings of a Symposium on the Interpretation of the Scriptures Held in Jerusalem, March 16-17, 1995). Ed. by F. Manns. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 59–68.

Marinov, D. [Маринов, Д.] (1981). Избрани произведения, Т. 1: Народна вяра и религиозни народни обичаи ed. by Маргарита Василева. София: Наука и изкуство

– (1984). Избрани произведения, Т. 2: Етнографическо (фолклорно) изучаване на Западна България: Видинско, Кулско, Белоградчишко, Ломско, Берковско, Оряховско, Врачанско ed. by Мария Велева. София: Наука и изкуство

Marinov, V. [Маринов, В.] et al. (1955). Принос към изучаването на бита и културата на турското население в Североизточна България Известия на Етнографския институт с музей 2:96–216.

Maykov, L. N. [ (Майков, Л. Н.] (1869). Великорусские заклинания Санкт Петербург: Типография Майкова

Melikoff, I. (1992). Sur les Traces du Soufisme Turc: Recherches sur l’Islam Populaire en Anatolie. Analecta Isisiana 50. Istanbul: Isis.

– (1998). Hadji Bektach, un mythe et ses avatars: gen èse et évolution du soufisme populaire en Turquie. Islamic History and Civilisation 20. Leiden: Brill.

Meyer, M. and R. Smith, eds. (1999). Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mikov, L. [Миков, Л.] (2005). Изкуството на хетеродоксните мюсюлмани в България (16–20 век): Бекташи и Къзълбаши / Алевии [The Art of Heterodox Muslims in Bulgaria (XVI–XX cent.): Bektaş and Kizilbaş / Alevi]. София: Академично издателство Професор Марин Дринов

– (2007). Култова архитектура и изкуство на хетеродоксните мюсюлмани (XVI–XX век): Бекташи и Къзълбаши / Алевии [Cult Architecture and Art of Heterodox Muslims in Bulgaria (XVI–XX cent.): Bektaş and Kizilbaş / Alevi]. София: Академично издателство Професор Марин Дринов

Miladinovtsi (1861). Бѫлгарски народни пѣсни собрани отъ братьа Миладиновци Димитрiя и Константина и издани отъ Константина въ Загребъ, въ книгопечатница-та на А. Якича Zagreb: Kнигопечатница-та на А. Якича

Mochul’skiĭ, V. [Мочульский, В.] (1886). Историко-литературный анализ стиха о Голубиной книгѣ. Русский Филологический Вестник 16(4):197–219.

– (1887). Историко-литературный анализ стиха о Голубиной книгѣ. Русский Филологический Вестник 17(1): 113–180; 17(2): 365–406; 18(3): 41–142; 18(4): 171–188.

– (1894). Слeды Народной Библiи в славянской и древне-русской письменности. Записки Императорскаго Новороссiйскаго Университета 61:1–282.

Nagy, I. (2006). The Earth-Diver Myth (Mot. 812) and the Apocryphal Legend of the Tiberian Sea. AEH 51(3–4):281–326.

– (2007). The Roasted Cock Crows: Apocryphal Writings and Folklore Texts. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 36:7–40.

– (1986–1988). Adam and Eve: the Myths of the Creation of Eros. AEH 34(1–4): 17–47.

Niditch, S. (1985). Chaos to Cosmos: Studies in Biblical Patterns of Creation. Chico, California: Scholars Press.

– (1993). Folklore and the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

– (1996). Oral World and Written Word: Ancient Israelite Literature. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

– (2000). A Prelude to Biblical Folklore: Underdogs and Tricksters. Urbana, Chicago: Univ. of Illinois Press.

Noort, E. and E. Tigghelaar, eds. (2002). The Sacrifice of Isaac: The Aqedah (Genesis 22) and Its Interpretations. Leiden: Brill.

Norris, H. T. (2006). Popular Sufism in the Balkans: Sufi Brotherhoods and the Dialogue with Christianity and Heterodoxy. London and New York: Routledge.

Obolensky, D. (1948). The Bogomils: A Study in Balkan Neo–Manichaeism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olsson, T., E. Özdalga, and C. Raudvere, eds. (1998). Alevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social Perspectives. London: Curzon Press.

Partridge, E. (1966). Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Macmillan.

Popova, A. (1995). Le Kourban, ou sacrifice sanglant dans les traditions Balkaniques. Europaea: Journal of the Europeanists 1(1):145–170.

Popruzhenko, M. G. [Попруженко, М. Г.] (1936). Козма Презвитер: болгарский писатель 10 века. (= Български Старини, Кн. 12). София: Придворна печатница (Издава Българската Академия на науките)

Pypin, A. [Пыпин, А.] (1862). Памятники старинной русской литературы, издаваемые Графомъ Григориемъ Кушелевымъ-Безбородко. Выпуск третiй. Ложныя и отреченныя книги русской старины, собранныя А. Н. Пыпинымъ Санкт Петербург: Тип. П. А. Кулиша

Radchenko, K. [Радченко, K.] (1910). Этюды по богомильству Известия Отделения Русского Языка и Словесности Императорской Академии наук 15(4):73–131.

Ramsey, J. (October 1977). The Bible in the Western Indian Mythology. The Journal of American Folklore 90(358):442–454.

Rose, H. J. (April 1938). Herakles and the Gospels. The Harvard Theological Review 31(2):113–142.

Rozhdestvenskaia, M. [Рождественская. М.] (2000). “Сказание о двенадцати пятницах” (Подготовка текста, перевод и комментарий) in: Библиотека Литературы Древней Руси. Т. 3: XI–XII века. Ed. by Д. С. Лихачев, Л. А. Дмитриев, А. А. Алексеев, and Н. В. Понырко Санкт Петербург: Наука (РАН, ИРЛИ), 242–247, 392–395.

Ruger, H. (1991). Oral Tradition in the Old Testament. In: Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition. Ed. by H. Wansbrough. Journal for the Study of the New Testament: Supplement Series 64. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press (JSOT Press), 107–120.

Russell, J. (2009). The Rhyme of the Book of the Dove (Stikh o Golubinoi Knige): From Zoroastrian Cosmology and Armenian Heresiology to the Russian Novel. In: From Daena to D în. Religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt. Festschrift für Philip Kreyenbroek zum 60. Geburtstag. Ed. by Ch. Allison et al. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 141–208.

Ryan, W. F. (1999). The Bathhouse at Midnight: Magic in Russia. Sutton: Trowbridge.

– (2006). Ancient Demons and Russian Fevers. In: Magic in the Classical Tradition. Ed. by Charles Burnett and W. F. Ryan. Warburg Institute Colloquia 7. London and Turin: The Warburg Institute, 37–58.

Sabar, S. (2009). Torah and Magic: The Torah Scroll and Its Appurtenances as Magical Objects in Traditional Jewish Culture. European Journal of Jewish Studies 3(1): 135–170.

Schwarzbaum, H. (1982). Biblical and Extra-Biblical Legends in Islamic Folk-Literature. Beiträge zur Sprach- und Kulturgeschichte des Orients, Band 30. Walldorf-Hessen: Verlag für Orientkunde Dr. H. Vorndran.

Shankland, D. (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: the Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. London: Routledge.

– (2006). Structure and Function in Turkish Society: Essays on Religion, Politics and Social Change. Istanbul: The ISIS Press.

Shapkarev, K. A. [Шапкарев, К. А.] (1973). Сборник от български народни умотворения в 4 тома. Том IV: Български приказки и вярвания София Български писател

Smilyanskaya, E. B. [Смилянская, Е. Б.] (2002). “Суеверное письмо” в судебно-следственных документах 18 в. In: Отреченное чтение в России XVII—XVIII веков. Ed. by А. Л. Топорков and A. A. Турилов Москва: Индрик, 75–174.

Speranskiĭ, M. N. [Сперанский, М. Н.] (1899). Из истории отреченных книг (I): Гадания по Псалтири (Тексты Гадательной псалтири и родственных ей памятников и материал для их объяснения) [Памятники древней письменности и искусства CXXIX; monographic issue]. Санкт Петербург: Общество любителей древней письменности

Spier, J. (1993). Medieval Byzantine Magical Amulets and Their Tradition. The Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56:25–62.

Stoyanov, Y. (2000). The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

– (2001). Islamic and Christian Heterodox Water Cosmogonies from the Ottoman Period: Parallels and Contrasts. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 64(1):19–33.

– (2004). Problems in the Study of the Interrelations Between Medieval Christian Heterodoxies and Heterodox Islam in the Early Ottoman Balkan-Anatolian Region. Scripta & e-Scripta 2:171–217.

Sumtsov, N. F. [Сумцов, Н. Ф.] (1888). Очерки истории южно-русских апокрифических сказаний и песен. Киев: Типография А. Давиденко

Szwat-Gyłybowa, G. [Шват-Гълъбова, G.] (2010). Haeresis Bulgarica в българското културно съзнание на 19 и 20 век. София: Университетско издателство Св. Климент Охридски

Thackston, Wheeler M., ed. (1997). Tales of the Prophets [by] Muhammad ibn Abd Allah al-Kisai (Great Books of the Islamic World). Chicago: Kazi Publications.

Tikhonravov, N. [Тихонравов, Н.] (1863). Памятники отреченной русской литературы, собраные и изданые Николаем Тихонравовым Vol. 1, Санкт Петербург: Типография Товарищества «Общественная Польза»; Vol. 2, Москва: Университет-ская Типография (Катков и К).

Tolstaya, S. M. [Толстая, С. М.] (1998). О нескольких ветхозаветных мотивах в славянской народной традиции In: От Бытия к Исходу. Отражение библейских сюжетов в славянской и еврейской народной культуре. Сборник статей: Академическая серия, Вып. 2. Ed. by В. Я. Петрухин Москва: Центр научных работников и преподавателей иудаики в вузах “СЭФЕР,” Международный Центр университетского преподавания еврейской цивилизации (Еврейский Университет, Иерусалим), Институт славяноведения Российской Академии наук, 21–37.

Toporkov, A. L. [Топорков, A. Л.] (2005). Заговоры в русской рукописной традиции XV—XIX вв.: история, символика, поэтика Москва Индрик

Torijano, P. (2002). Solomon the Esoteric King: From King to Magus, Development of a Tradition. Supplement for the Journal of the Study of Judaism, Vol. 73. Leiden: Brill.

Tsepenkov, M. [Цепенков, М.] (1998–2011). Фолклорно наследство Т. 1–6. София: Академично издателство Професор Марин Дринов

Tsibranska-Kostova, M. [Цибранска-Костова, М.] and M. Raykova [M. Райкова] (2008). Богомилите в църковноюридическите текстове и паметници Старобългарска литература 39/40:197–219.

Turdeanu, É. (1950). Apocryphes bogomiles et apocryphes pseudobogomiles. Revue de l’histoire des religions 138(1): 22–52; 138(2): 176–218.

Turilov, A. A. [Турилов, А. А.] and А. V. Chernetsov [А. В. Чернецов] (2002). Отреченные верования в русской рукописной традиции In: Отреченное чтение в России XVII—XVIII веков. Ed. by А. Л. Топорков and A. A. Турилов Москва: Индрик, 8–72.

Uspenskiĭ, B. A. [Успенский, Б. А.] (1996). Дуалистический характер русской средневековой культуры (на материале Хожения за три моря Афанасия Никитина) In: Избранные труды. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Москва: Школа “Языки русской культуры”, 381–432.

– (2001). Россия и Запад в 18 веке. In: История продолжается (Изучение восемнадцатого века на пороге двадцать первого) ed. by С. Я. Карп Москва / Санкт-Петербург: Университетская книгa, 375–415.

Utley, F. L. (January 1945). The Bible of the Folk. California Folklore Quarterly 4(1): 1–17.

– (1968). Rabghuzi—Fourteenth-Century Turkish Folklorist: A Contribution to Biblical-Koranic Apocrypha and to the Bible of the Folk. In: Volks überlieferung. Festschrift für Kurt Ranke zur Vollendung des 60. Lebensjahres. Ed. by F. Harkort. Göttingen: Verlag Otto Schwartz, 373–400.

VanderKam, J. C. (1997). The Aqedah, Jubilees, and PseudoJubilees. In: The Quest for Context and Meaning: Studies in Biblical Intertextuality in Honor of James A. Sanders. Ed. by C. A. Evans and S. Talmon. Leiden: Brill, 241–261.

Veselovskiĭ, A. N. [Веселовский, А. Н.] (июнь 1886). Заметки к истории апокрифов (1): Еще несколько данных для молитвы Св. Сисиния от трясавиц Журнал Министерства Народного Просвещения 245(6):288–302.

Yassif, E. (2009). Intertextuality in Folklore: Pagan Themes in Jewish Folktales from the Early Modern Era. European Journal of Jewish Studies 3(1):57–80.

Yatsimirskiĭ, A. I. [Яцимирский, А. И.] (1913). К истории ложных молитв в южно-славянской письменности (VI–X). Известия Отделения русского языка и словесности Императорской Академии наук 18(4):16–126.

Yudin, A. V. [Юдин, А. В.] (1997). Ономастикон русских заговоров. Имена собственные в русском магическом фольклоре Москва: Московский общественный научный фонд

Zabylin, M. [Забылин, М.] (1880). Русский народ, его обычаи, обряды, предания, суеверия и поэзия Москва Издание книгопродавца Березина

Zhivkov, T. Iv. [Живков, Т. Ив.] and St. Boyadzhieva [Ст. Бояджиева], eds. (1993–1994). Български Народни Балади и Песни с Митически и Легендарни Мотиви, Т. 1–2 [= СбНУ 60; monographic issue]. София: Издателство на Българската Академия на науките

Zhivov, V. M. [Живов, В. М.] (1988). История русского права как лингво-семиотическая проблема. In: Semiotics and the History of Culture: In Honor of Jurij Lotman. Studies in Russian. UCLA Slavonic Studies 17. Ed. by M. Halle, K. Pomorska, E. Semeka-Pankratov, and B. Uspenskij. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers, 46–128.

Footnotes

See in this connection the discussion in Mochul’skiĭ (1886; 1887); Gaster (1887; 1900; 1915); Dähnhardt (1907; 1909); Utley (1945); Tolstaya (1998); Nagy (1986–1988; 2006; 2007). For a typological analysis of multilingual transmissions of Bible-related narratives in non-European traditional societies (with special emphasis on indigenous mythologies and folklore of Western American Indians, after their conversion to Christianity), see Ramsey (1977). On similar processes characterizing the domestication of Islamic textual traditions among the indigenous Gayo communities in highland Sumatra (Indonesia), see Bowen (1992, 495–516).

On the “narrators for the common folk” (quṣṣāṣ al-ʿāmm) as “popular theologians” consult the discussion in the Introduction to the English translation (by W. M. Thackston) of the eleventh century collection of the Tales of the Prophets attributed to Muhammad ibn Abd Allah al-Kisai (Thackston 1997, xvii–xxiv, xxviii). See also Schwarzbaum (1982, 9, 11–12, 62–75).

On Alevi communities and their social organization see Georgieva (1991); Shankland (2003; 2006, 19–26, 67–129, 134–146, 185–206) and Gramatikova (2011). See also Olsson, Özdalga, Raudvere (eds.) (1998) and Dressler (2013). Further on Islamic heterodox traditions see Birge 1937; Melikoff (1992; 1998); Mikov (2005; 2007) and Norris (2006); on Alevi poetry see Dressler (2003).

Excerpts of the Sevar Quran spiritual stanzas are published in the present volume; see Chapter 6. Similar vernacular usage of the term “Quran” among the Kizilbaş communities in the Rhodope mountains, South-Eastern Bulgaria, was noted by Frederick de Jong (1993, 206–208).

According to the Alevi anthropogonic scheme, “the four basic cosmic elements, water [Şeriat], air [Tarikat], fire [Marifet] and earth [Hakikat]” are related “to the four levels of being [ervâh] in Man: mineral [ruh-i cismani], vegetable [ruh-i nebati], animal [ruh-i haywani] and human [ruh-i insani]. When all four ervâh are annihilated and replaced by the ruh-i safi (the pure spirit) the stage of the Perfect Man [insan-ı kâmil] has been reached” (Jong 1989, 9). Further on the “four doors of enlightment” (Şeriat, Tarikat, Marifet and Hakikat) in Alevi tradition, see Shankland (2003, 85–86,187). See also the discussion in Crone (2012, 483–484).

The author’s translation.

For a thorough analysis of the semantic coverage of the term Tarikat (frequently used in conjunction with the term Şeriat) among the Alevis see Shankland (2003, 84–89, 99, 112–113, 116–118, 121, 139–140).

In Bulgaria, during the Soviet period, this top-rung position in the local government was usually assigned to a Communist Party member.

See earlier discussion in Badalanova (2008) and Badalanova Geller (2008). On orality and Biblical textuality see Kelber (1983); Aune (1991); Andersen (1991); Ruger (1991); Elman and Gershoni (2000); Kawashima (2004); Bauckham (2006); Grafton and Williams (2006); Hasan-Rokem (2009, 29–55); Sabar (2009, 135–169) and Yassif (2009, 61–73). On traces of oral traditions in parabiblical writings see Mochul’skiĭ (1894); Flusser (1971) and Adler (1986–1987; 2013). On Biblical folklore see Niditch (1985; 1993; 1996; 2000); see also Kirkpatrick (1988), as well as Brewer (1979) and Rose (1938). Dundes (1999), on the other hand, suggests that Holy Writ is, in fact, oral literature and advocates that the Biblical corpus should be considered “as folklore”; a similar approach is employed by him in the analysis of the Quranic text; see Dundes (2003).

They were performed by a particular social subclass of wandering blind minstrels [калеки перехожие].

The term used in vernacular genre taxonomy to designate this type of religious poem/song is “psalm” [пса́льма]; see Sumtsov (1888, 36); Speranskiĭ (1899, 7–9, note 5) and Fedotov (1991, 36). Significantly, “the Russian Tsar” David Eseevich / Avseevich [Давид Есеевич / Асеевич] (that is, “David, the son of Jesse,” to whom the authorship of the Psalter is traditionally attributed) features in many such chants as the “key-interpreter” of divine wisdom encapsulated in the allegorical language of the texts; see Mochul’skiĭ (1886, (16: 4): 216); Bezsonov (1861, 269–278) (texts № 76, 77). On the other hand, among Slavonic scribes the Psalter was often referred to as “Glubina” [Глубина], that is, “depth”; see Mochul’skiĭ (1887, (17:1): 138–139). Furthermore the same term was likewise employed to label The Discussion Between the Three Saints and The Apocalypse of John apocryphal writings. The use of similar genre taxonomy in relation to the Psalter on the one hand and Slavonic parabiblical literature [апокрифическая Библия] and oral spiritual stanzas [духовные стихи] on the other suggests that the latter were perceived as vernacular counterparts of Scriptures; see Mochul’skiĭ (1887, (17:1): 131–132, 136, 138–139; 1887, (18:3): 90–91). See also the following note.

The formulaic phrase Голубиная книгa may be rendered in some versions of the poem as Глубинная книгa; considering the specific semantic diapason of the Russian form for “depth” [глубь], meaning both “profundity” and “wisdom” (see the discussion above), the connotation of the term Глубинная книгa may be thus construed accordingly as “the Deep / Innate / Profound / Unfathomable / Impenetrable / Incomprehensible / Secret Book”; indeed, the spiritual poems marked by this title contain elaborate cosmogonies and anthropogonies relating profound “holy secrets” of Creation of the Universe and Man. They are written in a mysteriously sealed divine Book which descends from Heaven to Earth. Then again, as pointed out by James Russell, the form “dove” [голубь], “referring presumably to the Holy Spirit, may have been a narratio facilior for an original ‘depth’ [глубь]”; see Russell (2009, 142). Following this line of argument, it may be suggested that the stock phrase Голубиная книгa may also be interpreted as “The Book of the Holy Spirit.” Therefore, in the current text I am tempted to interpret the concept of “deep” (as applied to knowledge) as “spiritual wisdom.” See also the discussion in Rozhdestvenskaya (2000, 394). On the other hand, Istrin had argued that the Slavonic “глубина” was most probably a domesticated version of the Greek term Μαργαρίται, which was conventionally used to designate either the cycle of John Chrysostom’s homiles, Adversus Judaeos (the first translations of which appeared among the Balkan Slavs no later than the fourteenth century), or other related exegetical compilations. Indeed, in Slavonic tradition the term глубина was part of a specific terminological cluster within the corpus, used interchangeably with titles such as Маргарит, Жемчуг, Маргаритъ Златоустовъ, Жемчюгъ Златоустовъ, Жемчюжная Матица, Златая Матица, etc.; see Istrin (1898, 478–489). Further on the content of The Rhyme of the Book of the Dove see Mochul’skiĭ (1886; 1887); Lincoln (1986, 3–12, 21–25, 32, 144–145).

Further on the conceptualization of Russia as a “Holy Land” see Uspenskiĭ (1996, 386–392).

Cf. Fasmer (1986–1987, (2), 374–375) and Uspenskiĭ (1996, 387).

Cf. Gen 1: 26–28.

As in Gen 2:7.

A similar approach to the origin of human speech—from the breath of God blown into the human mouth—is attested in the apocryphal Apocalypse of Enoch (1 Enoch 14: 2–3).

Together with the interpretation of the autonym “Slavs” as the “People of the Word/Logos,” in many Slavonic sources (and especially those composed during the Romanticism) there circulated another ethnocentric etymological construct based on the phonetic similarity between the ethnonym Slověninъ (var. Slavěninъ) / Slověne (var. Slavěne) and the lexeme denoting “glory” (slava). Hence the ethnonym “Slavs” was interpreted as the “Glorious People”; see Ivanov and Toporov (2000, 418). It was employed as a powerful rhetorical device in home-spun publicist writings and political pamphlets concerned with issues related to independence movements, especially among the Balkan Slavs in the period of their National Revival.

See also the discussion in Ivanov and Toporov (2000, 417–418).

See Kiselkov (1942 [1921]) and Popruzhenko (1936, 1–80).

Gen 2: 18–24.

See SbNU 8 (1892, 180–181), text № 2 (Адам дава име на сички божи творения) and Tsepenkov (2006 (4), 19–20), text № 9. See also Badalanova Geller (2010, 40–42).

Recorded by Dobrovol’skiĭ in the second half of the nineteenth century in the former Smolensk Gubernia of the Russian Empire; see also the next note.

See Dal’ (1880 (1), 513): воскилицание изумленья, а иногда и указания: вот где, погляди-ка: напр. Ева где лежит во.

See Badalanova (1994, 18–19) (text № 35).

Coracles were still being used in Iraq until the 1930s.

Related accounts are published by some Russian folklorists; see for instance the legend recorded in the village of Knyazhevo [Княжево] in the Tambov region of the Russian Federation by S. Dubrovina (2002, 3) from the local storyteller Sergey Fedorovich Mazaev [Сергей Федорович Мазаев] (born 1915) and his wife Evdokiya Yakovlevna Mazaeva [Евдокия Яковлевна Мазаева] (born 1916).

Gen 22: 1–19.

Surah 37:99–110.

See SbNU 1 (1889: 27), text № 4; SbNU 2 (1890: 22–25), texts № 1, 2, 3, 4; SbNU 3 (1890: 38); SbNU 10 (1894: 11–12), text № 3; SbNU 27 (1913: 302), text № 211. See also Miladinovtsi (1861), text № 29; Bezsonov (1864, 12–31), texts № 531, 532; Zhivkov and Boyadzhieva (1993 (1), 364–373), texts № 484–494; see also Part 2 of the Appendix (p.

See Gen 22: 17.