Marriage and Money

On 9 January 1729, Lord Charles Cavendish

We begin this account of the new family with what we can speak of with confidence, money. Younger sons of the aristocracy customarily received £300 a year, which is what Charles received since 1725. His father intended for the annuity to be raised to £500 at his death, but he moved to plan ahead starting with Charles’s marriage. In addition his father granted him the interest on £6000 and eventually the capital itself.3

The marriage settlement of Charles

At the time of his marriage, Charles

From the time of his marriage, Charles could probably count on an annual income of around £2000. We get an idea of what this income meant from Samuel Johnson, a professional man who rarely made above £300, who said that £50 was “undoubtedly more than the necessities of life require.” A gentleman was said to live comfortably on £500 and a squire on £1000.7 Cavendish’s income enabled him to live comfortably, acquire books for his library, and pursue his scientific interests. Within the conventional financial arrangements of wealthy English families, the Cavendishes and the Greys combined to create what was in effect a modest scientific endowment for Charles.

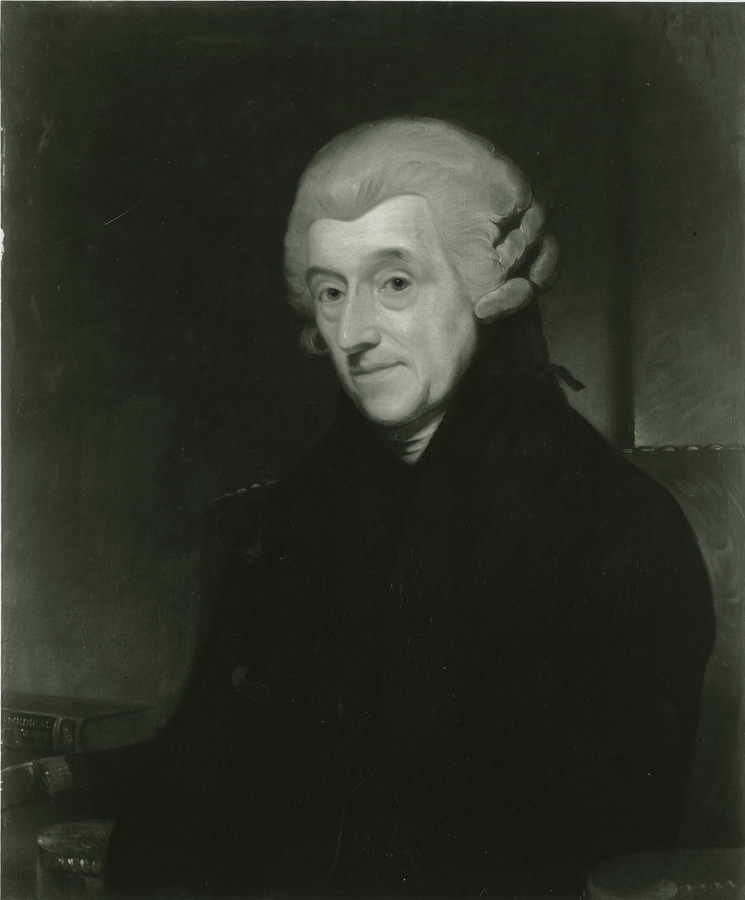

In addition to his active life in the city, at court, and in Parliament, Charles took on responsibilies in the Royal Society, serving on his first committee two years after his election.8 The portrait of him included in this book gives us an idea of what he looked like around then (Fig. 4.1). There are two portraits of Anne

They would not have gone there as conventional tourists, for although Nice did become popular with English tourists, this did not happen until the second half of the eighteenth century. In 1731, Charles Cavendish

Perhaps her health did improve. In any case, about three months after leaving Paris, Anne

In anticipation of Henry’s birth, Charles asked the British consul at Turin for help in obtaining permission from the duke of Savoy for “one of the Vaudois Protestant Ministers” to come to Nice to baptize the infant. No doubt Charles knew that the closest region in which the Protestant religion could be practiced was the valleys of the Vaudois in Piedmont. There was a family connection, if coincidental: the Vaudois Protestants, historically a persecuted group, kept in close touch with another persecuted Protestant group, the Huguenots, to whom Charles was related through the Ruvignys. Cyprian Appia

The next stage of Charles and Anne’s marriage is brief and ends sadly. A year and a half after their arrival on the Continent, they were back in France. From Lyon in the summer of 1732, Anne wrote to her father about her health and happiness

The Scientific Branch of the Family

Fig. 4.1: Lord Charles Cavendish. Father of Henry Cavendish. By Enoch Seeman. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Courtesy of the Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Photograph Courtauld Institute of Art.

Fig. 4.2: Lady Anne de Grey. Mother of Henry Cavendish. By J. Davison. Courtesy of the Bedfordshire Record Office.

They were going to Holland to see the great teacher and healer Herman Boerhaave

Fig. 4.3: The Honorable Henry Cavendish. Engraving by John Weale from a graphite and gray wash sketch by William Alexander. Cavendish refused to sit for a portrait. To get around this, Alexander, a draftsman in the China embassy, attended a dinner of the Royal Society Club, where he surreptitiously sketched Cavendish’s profile and separately sketched his coat and hat hanging on the wall. At home, he combined the two sketches into one. Persons who were shown it recognized Cavendish. Frontispiece of George Wilson (1851).

At some point Charles and Anne returned to England. Three months after her consultation with Boerhaave, Anne

Although for Anne who had reached her twenty-seventh year, life expectancy was over sixty in the eighteenth century, life then at any age was precarious. Hygiene was unknown, medicine was largely helpless, and death was indifferent to privilege. Henry and his brother Frederick grew up with one parent, a not uncommon fate under the prevailing conditions of life.21

Family of the Greys

As a widower, Charles kept in touch with Anne’s family

In 1740, Philip married Jemima Campbell, granddaughter of the duke of Kent. That same year the duke died, whereupon Jemima became Marchioness Grey and baroness Lucas of Crudwell. (Shortly before he died, the duke of Kent was made Marquess Grey with a remainder to his oldest granddaughter Jemima Campbell and her male heirs, establishing the only continuing title.) In the years to come, in the off-season Philip and Jemima lived at the duke of Kent’s country estate Wrest Park

Birch

Great Marlborough Street

In 1738, five years after his wife died, Charles Cavendish sold Puttteridge together with the rest of his country estate. To empower the trustees to make the sale, an act of Parliament was needed, and for that, a reason had to be given for wanting to sell; Cavendish said that Putteridge was too far from the rest of his estate. Parliament directed the trustees to sell the country estate for the best price possible.26

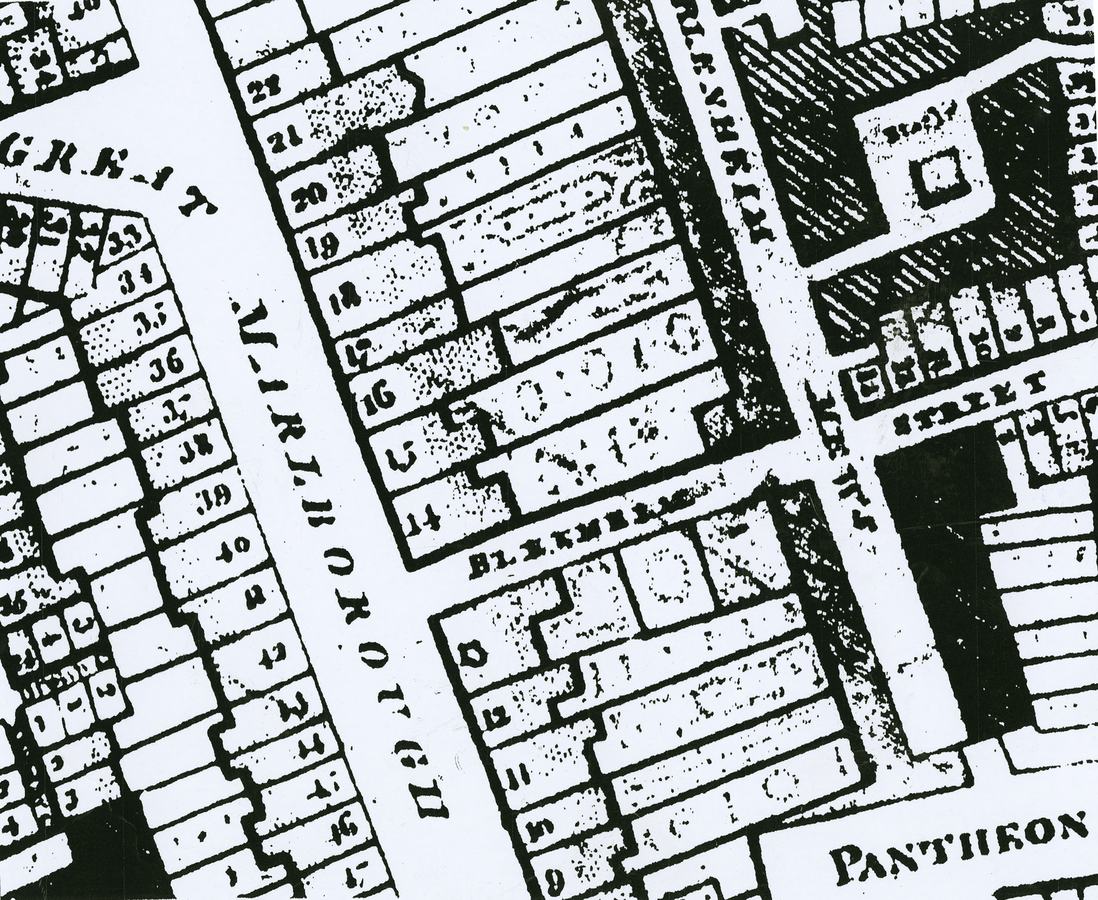

It would seem that the property sold for about what it had cost, and the price of the house Cavendish bought in its place that same year was only one tenth of that: for the absolute purchase of a freehold in Westminster, he paid £1750.27 The location was near Oxford Road, at the corner of Great Marlborough and Blenheim, streets named to commemorate a military action of the duke of Marlborough’s: a stone tablet in the wall read “Marlborough Street, 1704,” the year of his greatest victory, at the battle of Blenheim.”28 Later on, when rockets were observed in the middle of Great Marlborough Street, it was not to commemorate victory but to determine Cavendish’s longitude from Greenwich (Figs. 4.4–4.5).29

The inhabitants of Great Marlborough Street were gentlemen and tradesmen, about evenly balanced. In its plan, the street was atypical for London: long, straight, and broad, with a touch of Roman-like grandeur. Its drawbacks were that it opened onto no vistas, and its houses were undistinguished, giving the street a uniform, somewhat boring aspect. The house that Cavendish bought, number 13, was unusual in one respect: it was two houses, as it had been since around 1710, when John Richmond, who had actually fought at Blenheim and had risen to the rank of general, leased and joined the separate houses. Following the general’s death in 1724, the house went on the market as two houses in one. From a newspaper advertisement the next year, we learn of its size and layout. The property was 45 feet wide and 200 feet deep. Behind the house lay a garden, at the end of which was an apartment with a passageway to the house. The apartment was advertised as “beautiful” and “newly built,” with its own plumbing, underground kitchen, and four rooms on the single floor above. Adjoining the apartment were stables and a coach house. Parallel to Great Marlborough Street and running behind the house was a backstreet, Marlborough Mews (in 1799 Blenheim Mews), giving access to stables and an apartment adapted from stables, or “mews.” We think that as an adult Henry Cavendish lived in this apartment, with the separate address 1 Blenheim St. Thomas Thomson, who knew Henry Cavendish, described his apartment as converted stables.30

Fig. 4.4: No. 13 Great Marlborough Street House. Demolished. View of the back premises of the house on Blenheim Street. This was Lord Charles Cavendish’s house from 1738 to the end of his life. Courtesy of the Westminster City Archives.

Fig. 4.5: Map of Great Marlborough Street. Detail from Richard Horwood’s Plan of London … 1792–99, updated to 1813. No. 13 on the corner of Great Marlborough and Blenheim shows a building at the end of the property, designated No. 1 Blenheim Street. There looks to be a divided garden between it and the main house. It seems that Henry Cavendish lived in the rear building.

In the manner described, Charles and Henry maintained partially separate establishments, though mail was sent to him at his father’s address on Great Marlborough Street.31 We find that the rate books for the property do not list Henry until the year Charles died, so that from an official standpoint, Henry lived with his father, who paid the rates. In the rate books for June 1783, two months after his father died, Charles’s name still appears beside the assessment for the apartment, but now Henry’s name is listed for Great Marlborough Street; notations in the book suggest that the premises behind the house and the main house were both empty.32

Two years after Cavendish bought the house on Great Marlborough Street, in 1740, he was elected to the local governing body of the parish, the vestry of St. James, Westminster

Friends and Colleagues

Like the house, the life of science on Great Marlborough Street was double. Here Charles Cavendish lived most of his life, and it was Henry Cavendish’s address for over half of his life. Here, together and individually, they carried out experimental, observational, and mathematical researches in all parts of natural philosophy.

The wider setting for the scientific activity on Great Marlborough Street was London

For most of Charles Cavendish’s life and for a good part of Henry’s, London was the center of scientific activity in Britain. Even in the second half of the eighteenth century, when much of the important scientific activity took place elsewhere, in the Scottish university towns and in the rising industrial towns such as Birmingham and Manchester, London remained “intellectually pre-eminent,” a “magnet for men with scientific and technical interests,” the “Mecca of the provincial mathematical practitioner.”35 Over half of the British men of science

The Royal Society

For convenience, the Club met on the afternoon of the same day the Royal Society met, Thursday, and when the Royal Society was not in session, the Club continued to meet without a break. Members of the Club did not have to be members of the Royal Society, but normally they were, and the president of the Club was always the president of the Society. Its membership was fixed at forty, though members could bring guests; when Cavendish was admitted, the usual number of members and guests at a dinner was about twenty in the winter and fourteen in the summer. The dinners, which were heavy (fish, fowl, red meat, pudding, pie, and cheese), were held for the first three years at Pontack’s and then, throughout Cavendish’s membership, at the Mitre Tavern

The Royal Society Club was certainly the most prestigious and probably the largest of the learned clubs in eighteenth-century London, of which there were many. Meeting to discuss science, literature, politics, business, or any other interest that drew men together, London clubs often had a more or less formal membership

Another group met at a private house located in the Strand. Charles

We have a record of fifteen dinners Cavendish

Cavendish is first mentioned in Birch’s diary in 1730 as if he were public news: “Ld Ch Cavendish resigns,”50 a reference clearly to Cavendish’s resignation as gentleman of the bedchamber to the prince of Wales. Birch’s first mention of a personal contact with Cavendish came six years later, in 1736. Their connection then was probably formal, since in that entry and in an entry a year later, Birch identified Cavendish as the brother of the duke of Devonshire.51 The occasion was Birch’s scholarship, for Birch recorded that Cavendish gave him original papers concerning his grandfather William Russell

A letter from Birch to Philip Yorke

To get a fuller idea of Cavendish’s social life, we look at who came to dinner at his house on 21 October 1758. He had eight guests, all professional men, all but one middle-aged, some but not all married. They were friends, not persons Cavendish brought together for introductions. They were all active fellows of the Royal Society, though none was on the Council at the time; Birch was a secretary of the Royal Society, and Cavendish was possibly a vice president (he had presided at one meeting that year). It is possible that the social evening was combined with a meeting for a special purpose, perhaps relating to the Royal Society, though the regular meetings of the Society had not yet resumed after the long summer recess. Cavendish, the only aristocrat, at fifty-four was the next-to-oldest member at the party. His senior by two years, Thomas Wilbraham

Among Cavendish’s guests that night were several very good scientific men. The year before, Cavendish had been awarded the Copley Medal, as earlier had two of his guests, Watson

Friends and Colleagues

Fig. 4.6: Thomas Birch. Painting by J. Wills, engraving by J. Faber, Jr. Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 4.7: William Watson. Painting by L.F. Abbot. Reproduced by permission of the President and Council of the Royal Society.

Fig. 4.8: William Heberden. Painting by Sir William Beechey, engraving by J. Ward. Wikimedia Commons.

Over the period for which we have a record of dinners, 1748 to 1762, Cavendish together with Birch

Cavendish was especially close to three of the above colleagues, Birch, Heberden

Like Birch, the physician Heberden met men of science more than halfway (Fig. 4.8). His goal was to make the College of Physicians a medical version of the Royal Society, a proper scientific body. He used his influence in the College—he took on the duties of counselor, censor, and elect, one of the powerful senior fellows who chose the president from among themselves—to establish a committee of papers and a journal modeled and named after the Royal Society’s, the Medical Transactions. Consistent with his belief that until a Newton appeared in the science of the animal world to discover the “great principle of life,” medicine had only one recourse, experience. He regarded his task as the patient and laborious assembling of facts; a painstakingly accurate observer, he made no large generalizations (or discoveries). Despite his admonitions to physicians to publish, he himself was reluctant to do so. His high reputation was based on his medical practice and his knowledge of the classics, a combination then in irreversible decline. Upon being asked what physician he wanted in his final illness, Johnson called for Heberden, “the last of our learned physicians.”61

More than any other member, Watson

We learn more about Cavendish’s

To further a candidate’s chances of election, other members could add their signatures to the sheet. Ten, not an uncommon number, signed Henry Cavendish’s certificate in 1760. Occasionally there was a groundswell of enthusiasm for a candidate, as there was for Captain James Cook, whose certificate was signed by twenty-five members, including Henry Cavendish. Certain members constantly put up candidates, bearing a good share of responsibility for the early rapid growth of the Society. In the first forty years, the number of ordinary members tripled to three hundred, with the number of foreign members growing even faster, rising to almost half the number of ordinary members.64 During the twenty-five years that Cavendish recommended candidates, the growth of the Society markedly slowed. Cavendish’s own contribution was moderate: between 1734 and 1766, he recommended twenty-eight candidates, fewer than one a year.

Birch, who recommended a large number of candidates, on the order of a half dozen a year, signed recommendations with Cavendish more often than any other member, nineteen times.65 Next came Folkes

We turn to the candidates Cavendish recommended. In 1753 the Council resolved that candidates were to be known “personally” to their recommenders, a practice which in the past had usually been followed though not invariably.66 We can be reasonably certain that Cavendish was familiar with most if not all of the persons he recommended. Seventeen of the certificates he signed said that the candidates were proficient in the sciences, designated variously as natural philosophy, experimental philosophy, natural knowledge, natural history, philosophical knowledge, philosophy, and various branches of science; six certificates mentioned mathematics, three useful learning, two mechanics, and another two astronomy. Seven of the candidates were said to be distinguished in literature or polite learning, though never that alone. There were a few other accomplishments: antiquities, architecture, medicine, anatomy, musical theory, and (not very helpful) learning and knowledge. Two candidates were professors at Cambridge and Oxford, about whom nothing more needed to be said than the names of their professorships, which in their cases were astronomy and experimental philosophy. For one other candidate no explanation was given other than his position, an underlibrarian at the British Museum. Cavendish recommended three foreign members, whom he did not have to know personally, only their work. They were a French astronomer and two French authors of a commentary on Newton’s Principia. The persons Cavendish helped to gain entry into the Royal Society favored the physical and mathematical sciences, as might be expected, but they were not narrowly identified with particular fields, a generality which is also to be expected given the composition of the Society.

With one exception, every candidate Cavendish recommended was elected. The exception was the first candidate, a surgeon whose rejection may have been due to a general suspicion of surgeons in the Society. In 1734, Cavendish joined Sloane, two others, and John Stevens, one of the surgeons to the prince of Wales, to recommend John Wreden

A historian of science has placed Cavendish in a small group of fellows of the Royal Society who in the 1750s and 60s acted in concert, especially in the election of officers. Described as the “Hardwicke Circle” owing to the patronage of the first

Relatives

As he grew up, Frederick Cavendish

Of how Frederick occupied himself in the years after his accident, there is no record, but we have his father’s view of his mental “state.” As was the custom, in married settlements the younger son Frederick’s eventual prosperity was looked after by his mother, who at her death in 1733 left him her one quarter share of the duke of Kent’s Steane estate. This was sold and converted into stock, which was placed in the hands of trustees. In 1772 the last surviving trustee, Lord William Manners

Charles Cavendish took on responsibilities for his siblings. James, the brother with whom Charles had traveled abroad as a youth, was the older of the two, but he deferred to Charles in family matters, asking Charles to dispose of their mother’s estate and giving him power of attorney in all matters of their joint executorship.75 The reason was, at least in part, that as colonel of a foot regiment

William

William

Like his son William, the third duke’s daughters made advantageous marriages. Rachel

Charles Cavendish assumed various obligations for the women of his family. Together with his uncle James

Through another family member, a younger first cousin, Charles Cavendish

Holker Hall

Holker Hall is a grand manor on the northwest coast of England, in the county of Cumbria, formerly in Lancashire (Fig. 5.3). It is situated among splendid gardens on hilly park-like grounds with woodlands overlooking Morecambe Bay (Fig. 5.4). Built in the sixteenth century, it was altered in the 1780s and again in the next century. Today it belongs to the Cavendish family and is open to the public. Its library contains many books from Henry Cavendish’s library.

Late in life, Henry Cavendish had a conversation with a colleague John Barrow about Holker Hall

It is at odds with published sources, which agree on a succession of ownership of Holker Hall, in which Charles and Henry Cavendish do not enter. According to this version, Holker Hall came into the Cavendish family in 1756, when Lord George Augustus Cavendish acquired it from a Lowther cousin. When Lord George Augustus died in 1794, it passed to his brother Lord Frederick. When Lord Frederick

The relevant history begins with the last Lowther to live at Holker Hall, Sir Thomas Lowther

Charles often saw his sister Elizabeth

Elizabeth declined the executorship, and William asked Charles Cavendish

Problems naturally came up, the first of which was Fletcher, who was slow to understand and made mistakes in his accounts, causing Cavendish “a great deal of trouble.”104 He was told to prepare as soon as possible a “perfect state of all the effects whatsoever belonging to Sir Thomas at his death & all of the sums due from him at that time.”105 Cavendish was dissatisfied with the result: “I can’t suppose you think it [what Fletcher sent him] such an account as I asked for, nor such as is necessary for me to have in order to know the true state of Sr Thomas’s affairs.” The next month he wrote again, explaining how to make up his accounts. “I think this method necessary for the regularity of my own accounts in which I must enter a state of all moneys due to the personal Estate of Sr Th. Lowther at the time of his death & of all debts then due out of it.”106 Cavendish repeated his instructions over and over. Fletcher was old and ill, and in the spring of 1746, he died, succeeded by his capable son-in-law, William Richardson

Cavendish’s sister and now widow Elizabeth needed care. He paid sums to “Dr Mead,” likely the London physician Richard Mead

Cavendish kept on friendly terms with his ward. When Sir William—after his father he was baronet—was at the university, Cavendish sent him books he asked for. He introduced William to his society, inviting him to dinner at his house with scientific friends.111 In 1753 William was appointed lord lieutenant of Westmoreland, and in 1755 he succeeded his relative Sir James Lowther

Sir James Lowther was born in London and educated at Oxford and Middle Temple. Through inheritance, he became owner of valuable collieries and other properties around Whitehaven in Cumberland, on the northwest coast of England. He expanded his estate, lived frugally, and in time grew immensely rich, reputed to be the richest commoner in England. He made important improvements in the extraction and trading of coal, encouraged the production of iron in Cumberland, improved the harbor at Whitehaven, making it a major port for shipping coal, adopted technical improvements at his collieries, and was the first to install a Newcomen steam engine in Cumberland. After a visit to Whitehaven, Richardson said that he “did not imagine to have found so many new contrivances.”112 Lowther’s colliery steward Carlisle Spedding

Thomas had been close to James; they corresponded regularly, and Thomas paid visits to Whitehaven.116 James

In the spring of the following year, 1756, William Lowther contracted scarlet fever. Katherine, wife of the recently deceased third duke of Devonshire, wrote to the fourth duke William that “every body is in great pain for Sr Wm Lowther.” He had been ill for a week or ten days, attended by “Shaw & Heberden.” The day she wrote, William had had “a very bad night,” and his doctors had called in “Willmot,” who ordered more blisters. She wrote a postscript to the letter, saying that Charles Cavendish was just there to tell her that Sir William had died.118 On the same day, the duke received a consoling letter saying that persons who knew William thought he had “left the Chief part of His fortune to Your Brothers.”119 The “Chief part of His fortune” referred to Holker Hall, which we return to below.

A second Sir James Lowther

In his will, William named his former guardian Charles Cavendish as his executor.123 He left his money, stock, goods, chattels, and personal estate not otherwise specified to Cavendish in trust to pay for his funeral expenses and his legacies and to pay off his debts. What remained of the personal estate after these payments he left to Cavendish as his executor. Because he lived in London, Cavendish depended on the steward at Holker, Richardson, to provide him with information he needed from William’s estate at both Holker and Whitehaven. His letters to Richardson tell us about his actions and problems. Other than for the pictures, which were to remain in Holker Hall, none of the furnishings in any of William’s houses was specifically given in his will, so “the whole” belonged to Cavendish. That was the easy part. He needed to know what particulars belonged to William’s personal estate and what their values were and which of them young Sir James wanted to buy. Because much of William’s estate was in Cumberland, he depended on John Spedding, steward to the late James Lowther and after him to the late William at Whitehaven. To keep the money coming in, Cavendish allowed Spedding to continue to use what he needed from the personal estate to carry on the coal trade. He told Richardson to go to Whitehaven and talk to Spedding to learn what at the collieries belonged to William’s personal estate. He sent him off with a list of particulars that he thought belonged.124 Cavendish set about with evident total confidence to settle the affairs of this complex estate.

There was a difference of opinion on who owned the steam engines at the pits, and on the value of the ships and of the leasehold collieries and estates. Cavendish confided to Richardson his concern about having to depend on Spedding for valuations, asking how much trust he could place on the accounts he received from him. He understood that Spedding would be partial to the owner of that estate, who was then young James, but he was “intitled to a full discovery [of all Sir Williams personal estate] by Law as well as from the principles of justice.” In all disputes of interest, he told Richardson, it was his “desire to act with perfect openness & candour,” having “not in the least desire to get anything which I am not justly intitled to.” He suspected that measurements of the quantities of some stores “may not have done me strict justice,” but he did not know what to do about it other than to insist that Spedding give him strong assurances of the “truth” of the inventory before signing an agreement with him. Richardson thought that some of the prices Cavendish demanded were too high. Cavendish told him that he had no objection to lowering them if he saw fit, explaining that he did “not desire to have a farthing more than I have a right to.”125 Charles Cavendish spoke of “principles of justice,” “strict justice,” “openness,” candor,” and “truth.” We meet these words again in his son Henry’s business affairs.

From letters to his steward, we see the estate from Cavendish’s point of view. We have another point of view from Catherine Lowther

We come to a major disagreement, which had to do with £30,000 in New South Sea Annuities that were put in trust to finance the transfer of William’s estate to young James. Cavendish thought that the annuities were his because the transfer could not take place in the specified time, James not being of age. In July 1756, Cavendish and James agreed that the latter would bring a bill in the Court of Chancery against Cavendish to “have the right relative to the 30,000” and also the right relative to the leasehold estates and the steam engines and other equipment that went with them. Cavendish and James agreed on two other points: Richardson and Spedding between them would decide the values of the collieries and the furniture in the house at Whitehaven; and the legacies would be paid and the personal estate and the stock would be given to James when he came of age, while in the meantime he would receive dividends.130 Upon reading the agreement, Catherine wrote to her son, “I think most of it very unreasonable,” in keeping with “His Lords conduct.”131

We will look at Cavendish’s claims, for they show his hardheaded determination to acquire what he believed he was entitled to, even if only because of a legal technicality. Cavendish agreed that by Sir James’s will, young James was entitled to the properties in Cumberland (with the exception of houses and land in Cockermouth) and to all of the stocks except the £30,000 in New South Sea Annuities. The main issue was whether this sum fell back into the stock from which it was taken (James’s case) or whether it was separated and fell into the residue (Cavendish’s case). Cavendish insisted that the £30,000 belonged to him as part of the residue of William’s estate, since William died before young James was twenty-one, making the exchange of estates impossible. Cavendish also insisted that Sir James’s leasehold estates in Cumberland, consisting mainly of coal mines together with steam engines and other equipment affixed to the estates, passed to him as William’s residuary legatee. The cases were debated, and council on both sides was heard. The court decided that the £30,000 in annuities and James’s leasehold properties belonged to James, and that Cavendish had to pay over the interest from the annuities to James. Whether the steam engines and so forth stayed with the land or went to the Cavendish as executor was left to the opinion of the master of the rolls. Cavendish appealed the decision.132

Repeatedly in his letters to Richardson, Cavendish used the expression “what belongs to me,” or its equivalent. His letters read as though he was furthering his own interests, and that is how we originally read them.133 But this was his way of speaking: he meant by it, what belonged to him in trust for uses specified in the will, with anything left over going to him as specified in the will. He administered a very large estate, and he went about it with his customary conscientiousness. There is another consideration. William was generous—he tripled Spedding’s

When Catherine Lowther

To this point, we have not looked at what William placed at the head of his will and gave most attention to, Holker Hall. William left this house along with other manors, buildings, and lands to William Cavendish third duke of Devonshire and his eldest son “to the several uses upon the trusts.” Holker Hall was to go first to his own male offspring, of which he had none, in which event it was to go to his aunt Catherine Lowther for her “use” over the course of her life; and upon her death, the estate was to pass to George Augustus Cavendish

Not long after William died, Cavendish heard from friends of Catherine Lowther “that she has thoughts of making over the estate to Lord George Augustus Cavendish for a proper consideration.”146 This evidently was soon done. Lord George became the first male Cavendish to live at Holker Hall, making it his home for nearly forty years, until his death in 1794. In his final will he spoke of “the person or persons who shall upon my decease succeed and become entitled to the said House [Holker Hall]and Estate at Holker,”147 wording which might suggest that there was uncertainty about his successor, but as directed by William Lowther’s will Holker Hall went next to Frederick Cavendish, who held it until his death in 1803.

Nowhere in William’s will is Charles Cavendish said to be entitled to Holker Hall, nor is he in George Augustus Cavendish’s and Frederick Cavendish’s wills. If what Henry Cavendish told John Barrow is correct, that Holker Hall was left to his father and his father left it to him, it is unlikely that his father acquired it from George Augustus Cavendish as Henry said it did; for by Sir Williams’s will, Frederick Cavendish was next in line. When Frederick died, his younger brother John, who was next in line, was already dead, and the beneficiaries named in Sir William’s will came to an end. If there was uncertainty, it may have come at this juncture, but so far as we can judge from his will, Frederick did not think there was any uncertainty, treating Holker Hall no differently than the rest of his property. With the exception of special legacies, he left “the Capital messuage or mansion house of Holker Hall with the park lands and hereditamenti” in the parish of Cartmel, Lancashire, together with his other properties to his nephew George Augustus Henry Cavendish and his heirs and assigns.148 This George was also Henry Cavendish’s principal heir and the Lord George that Henry told Barrow

There are three possible reasons why Henry Cavendish’s ties to Holker Hall remain elusive. One is that we have missed something, either a document that has not yet been found or a right that a legal scholar would understand. Another is that Barrow’s recollection is wrong, though it seems unlikely that he would remember Cavendish having said that he owned the manor if he did not say it. Third, Cavendish was confused about the ownership. He was normally very accurate, and we do not consider this possibility lightly. But let us see. To begin with, he certainly knew about his father’s involvement with the Lowthers. When Charles Cavendish was appointed administrator of Thomas Lowther’s estate in 1745, when he was Sir William’s guardian in 1745–48, and when he became executor of Sir William’s estate in 1756, Henry was fourteen to seventeen, and twenty-five. He was away at school for part of the time, but at other times he was home, and he would have known that his father made journeys to the Lowther properties and why. Later he himself was involved: Charles Cavendish and after him Henry were trustees of Cartmel Rectory, part of the Lowther estate: the bishop of Chester leased Cartmel Rectory to Henry Cavendish in trust for the persons entitled to it under Sir William Lowther’s will, who were the persons entitled to Holker Hall, George Augustus Cavendish and Frederick Cavendish

Footnotes

George Edward Cokayne (1982, 3: cols. 173–174).

Charles had just turned twenty-one when on 6 April 1725 his father settled on him a £300 annuity. He had use for it, for one week later he was returned as M.P. for Heytesbury. The £6000 paid 3.5% interest. The £500 annuity and the £6000 capital were determined by an earlier settlement, in 1678. Devon. Coll., L/13/9, L/19/31, L/19/33, and L/19/34.

Devon. Coll., L/19/33. H.J. Habakkuk (1950, 15–16, 18, 20–24). J.H. Plumb (1963, 72).

Charles Cavendish appears on the poor rolls of Westminster Parish of St. Margaret’s in 1728, paying £5.5.0 annually, the same as the duke of Kent, his father-in-law, who had a house in the parish. Westminster Public Libraries, Westminster Collection, Accession no. 10, Document no. 343. Charles’s address in 1729–32 was 48 Grosvenor Street, a three-story, brick, terrace house, with four windows on each floor, and with touches of elegance: extensive panelling, marble chimney pieces, and a “Great Stair Case” in the entrance hall. British History Online, “Grosvenor Street South” (http://www.british-history.ac.uk).

Devon. Coll., L/19/33 and L/5/69.

George Rudé (1971, 48, 61).

On 17 July 1729, Cavendish was appointed to a committee to inspect the library and the collections. It met every Thursday from 24 July until 6 Nov. 1729, and on 11 Dec. it was ordered to continue its work. Minutes of Council, Royal Society 3:28–30, 34–36, 39, 55–56, 114–116.

July 1728. House Account. To ye 28 December 1728,” Bedfordshire Record Office, Wrest Park Collection, L 31/200/1.

Sophia, duchess of Kent to Henry, duke of Kent, 21 Feb. 1729/1730, Bedfordshire Record Office, Wrest Park Collection, L 30/8/39/5.

James was at least abroad at the same time as Charles. On 10 Oct. 1731, James “came to Town from France.” Weekly Register, Oct. 16, 1731. BL Add Mss 4457, 76.

Anne Cavendish to Henry, duke of Kent, 4 Nov. [1730], Bedfordshire Record Office, Wrest Park Collection, L 30/8/11/1.

Henri Costamagna (1973, 26). Daniel Feliciangeli (1973, 55–56). Anon. (1934, 660–663).

“Nice,” Encyclopedia Britannica (Chicago: William Benton, 1962) 16: 414–15).

Anne Cavendish to Henry, duke of Kent, 22 June [1732], Bedfordshire Record Office, Wrest Park Collection, L 30/8/11/2.

Bolingbroke wrote to his half sister Henrietta, “I was yesterday at Leyden to talk with Doctor Boorehaven, and am now ready to depart for Aix-la-Chapelle.” Letter of 17 August 1729, in Walter Sydney Sichel (1968, 525).

Anne Cavendish to Henry, duke of Kent, 22 June [1732]. G.A. Lindeboom (1974, 18); (1970, 227–228).

Four days later, on 24 September 1733, Anne Cavendish was buried in the Grey family vault at Flitton. “Extracts from the Burial Register of Flitton,” Bedfordshire Record Office, Wrest Park Collection, L 31/43. We assume that she died of her lung illness, though it could have been related to giving birth.

Stone (1982, 46–48, 54, 58–59).

Albert E. Gunther (1984, 8, 35).

There are many letters from Thomas Birch to Philip Yorke reporting on scientific news between 1747 and 1762, in BL Add Mss 35397 and 35399. Thomas Birch to Jemima, marchioness de Grey, 12 Aug. 1749, BL Add Mss 35397, ff. 200–201.

Gunther (1984, 35–39).

We do not know the frequency of Charles Cavendish’s visits to his wife’s family. We do know that he and Birch were at the Grey’s together twenty-six times between 1741 and 1751, on two of which occasions, Henry Cavendish came with his father. He was nine and ten at the time. Thomas Birch Diary, BL Add Mss 4478C.

“An Act for Discharging the Estate Purchased by the Trustees of Charles Cavendish … from the Trusts of his Settlement, and for Enabling the Said Trustees to Sell and Dispose of the Same for the Purposes Therein Mentioned,” Devon. Coll.

“Assignment of two Messuages in Marlborough Street from the Honourable Thomas Townsend Esq. to His Right Honourable Lord Charles Cavendish,” 27 Feb. 1737/1738, Chatsworth, L/38/35. London County Council (1963, vol. 3, pt. 2:261–256).

“Explosions of Rockets Observ’d at Lord Charles Cavendish’s. The Middle of Gr. Marlbro St.,” Canton Papers, Royal Society 2:13.

London County Council (1963, vol. 3, pt. 2:256) Richard Horwood (1966). Thomas Thomson wrote that Cavendish’s “apartments were a set of stables, fitted out for his accommodation.” (1830–1831, 1:59).

James Clerk Maxwell in Cavendish (1879, xxviii).

Charles Caverndish was assessed rates for his house on Great Marlborough Street based on a rent of £90; his house being double and also end-of-row, his assessment was more than double that of other occupants on his side of the street. Beginning in 1774, he was also assessed rates for the back mews. Rate books Great Marlborough Street/Blenheim Street, parish of St. James Westminster Archives, film nos. D64, D72, D87, D673, D683, D708, D1102–1110, D1260–1265.

From Cavendish’s election to the vestry on 26 Dec. 1740 (D 1760, 145) to his last meeting on 13 Feb. 1783 (D 1764, 518), Minutes of the Vestry of St. James, Westminster, D 1760–1764, Westminster City Archives. Cavendish had other duties in the parish; he was a trustee, for example, of the King Street Chapel (also known as Archbishop Tenison’s Chapel) and its school and met with other trustees at the end of the year to pass the accounts. Great Britain, Historical Manuscript Commission, (1923, vol. 3, 270 (4 Jan. 1742/1743), 306 (4 Jan. 1744/1745)). London and Westminster were geographically distinct until the sixteenth century, when the cities spread onto the fields separating them.

Quoting an acquaintance on the importance of living in London: James Boswell (1963, 3:73). Rudé (1971, 4–7, 25, 28, 32–33).

Cavendish, as son of a peer, was admitted under a special rule of privilege; persons from the lower orders were not admitted at all; and only “rich Philosophers” could afford to pay its admission fee of twenty-two guineas. John Smeaton to Benjamin Wilson, 7 Sep. 1747, quoted in Larry Stewart (1992, 251).

Richard Sorrenson (1996, 33, 35).

T.E. Allibone says that the Royal Society Club was continuous with “Halley’s Club,” for which he has several pieces of evidence, but for his assertion that Charles Cavendish was probably a member of Halley’s Club he offers none, and so this lead we are unable to follow up. T.E. Allibone (1976, 45, 97). An opposing view of Halley’s part in the origins of the Club is Archibald Geikie (1917, 6–9). Charles Cavendish was elected to the Club on 25 July 1751 and he became a member on 9 January 1752.

28 Nov. 1751, Minute Book of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society. Cited in Allibone (1976, 44–45). Cavendish was a member of the Club for twenty-one years, resigning at the annual meeting in 1772. He continued to take an interest in it, making it a gift of venison five years later. 9 Sep. 1779, Minute Book of the Royal Society Club, Royal Society, 7.

19 Oct. 1736, Thomas Birch Diary. W. Warburton to Thomas Birch, 27 May 1738, in John Nichols (1817–1858, 2:86–88, on 88). Bryant Lillywhite (1963, 280–281, 369–370, 421–423, 595).

Parkinson (1854–1857, vol. 2, pt. 1, 221, 280, 322).

Request to be “admitted to the private meetings, of several learned Gentlemen, at Lord Macclesfield’s and Lord Willoughby’s.” Rodolph De Vall-Travers to Thomas Birch, [4 Apr. 1757], BL Add Mss 4320, f. 9.

Andrew Kippis’s life of the author published in John Pringle (1783, lxiii–lxiv). Kippis says that the group met at Mr. Watson’s. This Watson he identifies as a grocer.

“Ross or Rosse, John,” DNB, 1st ed. 17:266–267.

“Pringle, Sir John, ibid. 16:386–389, on 388.

“Baker, Sir George,” ibid. 1:927–29, on 928.

Dorothea Waley Singer (1949, 161–162).

Humphry Rolleston (1933, 412–413, 567–568).

12 Oct. 1730, Thomas Birch Diary.

29 June 1736 and 1 Aug. 1737, ibid.

1 Aug. 1731, ibid.

Thomas Birch to Philip Yorke, 18 Aug. 1750, BL Add Mss 35397. The guests were Birch, Folkes, Heberden, Watson, Thomas Wilbraham, and Nicholas Mann.

30 Nov. 1751, JB, Royal Society 20:571–573.

Birch’s Diary records dinners at which Cavendish was present at the homes of fourteen persons, all but one of whom were fellows of the Royal Society. The names are familiar: in addition to those mentioned above, they include Josiah Colebrooke, Mark Akenside, Daniel Wray, and William Sotheby.

Thomas Birch Diary. The number two hundred is a minimum, since Birch made his entries hastily, not always giving the names of everyone he dined with. Cavendish’s name was probably among those he sometimes omitted.

Gunther (1984, 13–19). Thomas Birch (1744, 113–114, 304–307).

C. Barton to Thomas Birch, 19 Sep. 1754, BL Add Mss 4300, f. 174. Thomas Birch’s Sermons, vol. 7, f. 188, BL Add Mss 4232C.

“Birch,” DNB 2:531.

Rolleston (1933, 414–417). Audley Cecil Buller (1879, 16, 21–22). William Munck (1878, 2: 159–164). William Heberden (1802, 483, and appendix, “A Sketch of a Preface Designed for the Medical Transactions, 1767,” 486–494).

“Watson, Sir William,” DNB, 1st ed. 20:956–958.

20 Aug. 1730, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 3:51, 77.

23 Nov. 1775, Certificates, Royal Society 3:237. Henry Lyons (1944, 125–126).

Between 1748 and 1760, Birch recommended seventy-six candidates. Royal Society, Certificates.

10 May 1753, Minutes of Council, Royal Society 4:118–119.

Joseph Priestley to John Canton, 14 Feb. 1766, Canton Papers, Royal Society 2:58. Priestley was elected that year without the help of Cavendish, Benjamin Franklin joining the other three instead. Joseph Priestley to Richard Price, 8 Mar. 1766, in Priestley (1966, 17–19, on 19).

Other members were Davall, Charles Yorke, and John Ward. Considered their successes in elections were Birch and Paul Maty as secretaries and Macclesfield, Morton, and Pringle as presidents of the Royal Society. David Philip Miller (1998, 75–77, 81, 89).

Henry Cavendish referred to “Fredy’s” letters and expenses in “Papers in Walnut Cabinet,” Devon. Coll.

Charles Cavendish’s legal case involving his marriage settlement and Frederick’s expenses, 30 Apr. 1773, Devon. Coll., L/114/32. Anonym, “Memoirs of the Late Frederick Cavendish, Esq.,” Gentleman’s Magazine 82 (1812): 289–91, on 289. Lord Hartington to the duke of Devonshire, 17 Aug. 1754, Devon. Coll., no. 260.119.

Charles Cavendish hosted a dinner at his house on 17 July 1754; the next time he dined with his friends was at Stanhope’s house on 2 Dec. of that year. Thomas Birch Diary.

Thomas Birch to Charles Cavendish, 17 Oct. 1754, BL Add Mss 4444, f. 180.

“Copy Case between Father and with Mr. Perryn,” 30 Apr. 1773. Charles Cavendish to S. Seddon, 27 and 29 July 1772. “Discharge from the Right Honourable Lord Charles Cavendish to John Manners Esqr as to Trusts for his Lordship and the Honourable Henry Cavendish & Frederick Cavendish His Sons,” Devon. Coll., L/14/32. The new trustees were Philip Yorke, earl of Hardwicke, and Charles’s nephews Frederick and George Augustus Cavendish. In his will, Charles left his son Frederick £4000 for his having received profits from his mother Anne’s estate and dividends from the stock bought with the money arising from the sale of that estate. Devon. Coll., L/69/12.

James Cavendish to Charles Cavendish, 25 Mar. 1727 and 23 Aug. 1732, Devon. Coll., no. 34/2.

Lists of subscribers to Abraham de Moivre, Miscellanea analytica de seriebus et quadraturis (London, 1730); Roger Long (1742, 1764, 1784, vol. 1); Colin Maclaurin (1748).

In a dispute over appointments between the duke of Devonshire and the duke of Newcastle, for example. Duke of Devonshire to Lord Hartington, 8 and 20 May, 15 and 24 June 1755, Devon. Coll., nos. 163.51,52,60, 62.

J.H. Plumb (1956–1960, 1:42–43, 235–236, 2:280).

John Pearson (1983, 89–91); quotation from Johnson on 90.

Lord Hartington to Dr. Newcome, 14 Dec. 1745; Charles Cavendish to duke of Devonshire, undated, Devon. Coll., nos. 260.58 and 211.3; John Whitaker to Dickenson Knight, undated [1745]; Ralph Knight to Dickenson Knight, undated [Dec. 1745]; John Holland to Ralph Knight, undated [1745], in Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission (1893, 164–165). Duke of Devonshire to Robert Wilmot, 25 Oct. 1745, in Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission (1925, 2:349). Richard Burden to [Viscount Irwin], 7 Dec. 1745, Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission (1913, 138).

Duke of Devonshire, “My Will,” 1 Oct. 1731, Devon. Coll., no. 163.95.

Pearson (1983, 93–103).

Charles Cavendish’s involvement is reflected in the statement of expenses presented to the third duke by Hutton Perkins, the duke’s lawyer, on 13 May 1748. Devon. Collection, no. 313.1.

“The scientist, Henry Cavendish, lived there [in Burlington House] for several years in his youth.” D.A. Arnold, Royal Society of Chemistry, “The History of Burlington House” (http://www.rsc.org/AboutUs/History/bhhist.asp). Royal Society of London (1940, 65). The owner of Burlington House, Richard Boyle, third earl of Burlington, is said to have had an interest in natural philosophy, but he is known for his interest in the arts and especially for his talent as an architect, being instrumental in introducing the Palladian style in Britain and Ireland. Horace Walpole called him “the Apollo of the arts.” When his daughter and heir Charlotte Elizabeth Boyle married William Cavendish, Henry Cavendish was about to begin his university studies. When the earl died in 1753 and Burlington House passed to his daughter, Henry Cavendish had completed his university education. It is unclear what connection Henry could have had with Burlington House. We know that Henry’s heir George Augustus Henry Cavendish used the house for at least two spells.

Entries for the second and third earls of Bessborough, in Brydges (1812, 7:266–267). Francis Bickley (1911, 207).

“Bond from His Grace the Duke of Devonshire to the Rt Honble Lord Charles Cavendish,” 22 Sep. 1743, Devon. Coll., L/44/12.

R. Landaff to duke of Devonshire, 6 Dec. 1755; Thomas Heaton to duke of Devonshire, 6 Dec. 1755, Devon. Coll., nos. 356.5 and 432.0. Theophilus Lindsey to earl of Huntington, 24 Dec. 1755. Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission (1928–47, 3:111–114, on 113).

“Probate of the Will of Ly Eliz. Wentworth 1741,” Devon. Coll., L/43/13. Lady Elizabeth was the widow of Sir John Wentworth of Northempsall. Seven years later, Charles and James Cavendish were released from any further claim on them as executors by another Lady Wentworth, Dame Bridget of York: “Ly Wentworths Release to Lady Betty Wentworths Executors March 5 1748.” Charles kept a notebook for Lady Betty’s personal estate for twenty years, from 1741 to 1761. After 1748 Charles and James regularly received a small dividend from 200 shares of South Sea stock. After James’s death, his part went to Richard (Chandler) Cavendish and, eventually, to Charles Cavendish.

“Deed to Exonerate the Estate of the Duke of Devonshire from the Several Portions of Six Thousand Pounds … to be Directed to be Raised for Lady Rachel Morgan, Lady Elizabeth Lowther and Anne Cavendish the Three Surviving Daughters of William Second Duke of Devonshire,” 28 July 1775, Devon. Coll., L/19/67. Charles Cavendish to John Heaton, 28 Aug. 1775, draft, and “Account of Deeds to Be Executed by Lord Charles Cavendish,” Devon. Coll., 86/comp. 1.

Brydges (1812, 1:356). Page (1971, 2:190). Geoffrey Holmes (1967, 222).

Articles on the marriage of William Jones and Elizabeth Morgan, daughter of Lady Rachel Morgan, to which Charles Cavendish was a party, 4 July 1767, Devon. Coll., L/43/16.

James Cavendish and Charles Cavendish together recommended Gowin Knight for fellowship in the Royal Society for his “mathematical and Philosophical knowledge,” 24 Jan. 1745, Certificates, Royal Society 1:14, f. 297.

“The Surname of Cavendish Witnessed by W. Goostrey All Proved by Mr Chandler 20th December 1751,” Devon. Coll.

Elizabeth Cavendish’s will, 26 Feb. 1778, Devon. Coll., L/31/37. In a codicil of 31 Jan. 1779, among other changes, she left her land to Dudley Long instead of to the duke of Devonshire, and she left her house in Picadilly to Charles Cavendish and Charles Camden to hold in trust for members of the Long family, especially Dudley.

“Lord Camden and the Honourable Henry Cavendish Assignment and Deed of Indemnity,” 31 Dec. 1783, Devon. Coll., L/31/37. “Copy of Mr. Pickerings Letter to Mr. Wilmot,” 26 Apr. 1780, ibid., L/86/comp. 1.

The first survey of the Lancashire estate in 1775, thirty years after Sir Thomas’s death, listed Cartmel-Holker at 2,860 acres and Furness at 3,559 acres. J.V. Beckett (1977b, 47–51).

Thomas Lowther to James Lowther, 8 Aug. 1728, Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/W/ 39.

Thomas Lowther to James Lowther, 26 Sep. 1728, ibid.

Edward Butler to John Fletcher, 16 May 1745, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/3/1.

Charles Cavendish to John Fletcher, 18 July 1745, draft, Devon. Coll., L/43/14. Charles was sworn in as administrator on 30 July 1745. Charles Cavendish to John Fletcher, draft, 30 July 1745, Devon. Coll., box 43/14. This bundle contains one notebook of Cavendish’s guardian account for William and two notebooks of his administrator’s accounts and correspondence for Thomas Lowther’s estate. Drafts of his letters to the estate stewards and copies (probably incomplete) of their letters to him are contained in this correspondence, 1745–48. Administrator appointment, 17 Aug. 1745, Devon. Coll., box 31/11.

Charles Cavendish to John Fletcher, 27 July 1745, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/5.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 13 Mar. 1746, draft, Devon. Coll., box 43/14.

Charles Cavendish to John Fletcher, 20 July [1745], Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/5.

Charles Cavendish to John Fletcher, 13 Aug. 1745, ibid.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 13 Mar. 1746, draft; Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 20 May 1746, draft; Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 20 May 1746, draft, box 43/14. William Richardson to Charles Cavendish, 2 May 1746, copy, ibid.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 21 June 1746; Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 27 Dec. 1746, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/7.

On his sister’s behalf he also paid “Mr. Duffield,” who received regular pavements up to £180 each time, and “Mrs. Potter.” Various dates in “Guardians Account” and in an untitled notebook containing six pages of accounts, 1745–48, Devon. Coll., box 43/14.

On 9 Jan. 1747, the steward, Danby, for the Yorkshire estate informed Charles that John Lowther had died. “Sr W. Lowther’s Estate,” Devon. Coll., box 43/14.

5 June 1753, Thomas Birch Diary.

Thomas Lowther to James Lowther, 6 June 1734, Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/W.

Cavendish signed Lowther’s certificate. 20 May 1736, JB, Royal Society 15:331.

Henry Newman to James Lowther, 26 Aug. 1732, Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/L1/1/53.

Thomas Lowther to James Lowther, 11 July 1734, ibid., D/Lons/W/37. There are many letters from Thomas to James Lowther in the Carlisle archive. Charles Cavendish also visited Whitehaven.

H. Fox to Lord Hartington, 4 Jan. 1755, Devon. Coll., no. 330.30.

K. Devonshire to duke of Devonshire, 15 Apr. 1756, ibid., no. 344.8. We assume the letter writer is Katherine, wife of the recently deceased 3d duke of Devonshire.

Ducannon to duke of Devonshire, 15 Apr. 1756, ibid., no. 294.46.

Beckett (1977b, 52). Also William left all of the buildings at Cockermouth, near Whitehaven in Cumberland, to Charles Cavendish to hold in trust for young James Lowther.

Theophilus Lindsey to Francis Hastings, 10th earl of Huntington, 25 May 1756, in Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission (1928–47, 3:117).

Horace Walpole to George Montagu, 20 Apr. 1756, in Walpole (1937–1983, 9:183–187, on 185).

Will of William Lowther, dated 7 Apr. 1755, probated 22 Apr. 1756, Devon. Coll., L/31/47.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 27 Apr., 13, 27 May 1756, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/7. Cavendish’s list: arrears of rent; bonds, notes, etc.; furniture, plate, etc.; coal debts; coals raised; wagons, carts, etc.; horses; tools; corn, hay, etc.; timber in yard; timber felled; material for buildings not used; ships; engines; leasehold estates & collieries.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 26, 29 June and 27 July 1756, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/7.

Catherine Lowther to James Lowther, 11 July 1756, Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/L1/61.

Catherine Lowther to James Lowther, 8 July 1756, ibid.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 8 May 1756, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/7.

Cavendish to Richardson, 27 Apr. 1756.

“Heads of What Is Agreed on between Ld Charles Cavendish & Sr James Lowther,” [before 19 July 1756], Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/L1/62.

Catherine Lowther to James Lowther, 19 July 1756, ibid., D/Lons/L1/61.

Packet of papers labeled in Henry Cavendish’s hand “Sr W. & Sr J. Lowther’s Wills & Papers Relating to the Law Suit between L.C.C. & Sr J. Lowther.” Devon. Coll., 31/17.

Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach (1999, 93–94).

Plus several small annuities.

Beckett (1977b, 64). Not all of James’s income would have gone to William. For example, he left his South Sea annuities to young James, who would have received the dividends. Sir James Lowther’s will, 1754, Devon. Coll., L/31/17.

Because of his very short life as a very wealthy man, not much can be learned. His income from 5 July 1755 to 25 May 1756 (the month after his death) was £11,640. His expenses were £8251, which included large payments to Girolamo Belloni, the head of a family bank in Rome. “Sr William Lowther Bart His Account with Robt Snow & Willm Denne 1755,” 5 July 1755 to 25 May 1756, Devon. Coll., box 43/14.

Cavendish to Richardson, 8 May 1756. Cavendish directed his steward to continue William’s generosity by distributing £50 to persons in the neighborhood who were most in need, as William would have done were he alive.

Catherine Lowther to James Lowther, Apr. 1756, Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle, D/Lons/L1/61.

Catherine Lowther to James Lowther, 28 Oct. 1756, ibid.

“Lowther, James, Earl of Lonsdale (1736–1802),” DNB, 1st ed. 12:217–220, on 219.

Horace Walpole to George Montagu, 20 Apr. 1756, in Walpole (1937–1983, 9:184–185).

William Lowther’s will, 7 Apr. 1755, probated 22 Apr. 1756, Devon. Coll., L/36/47. He died on 15 Apr. 1756.

Charles Cavendish to William Richardson, 28 Dec. 1756, Lancashire Record Office, DDCa 22/7.

George Augustus Cavendish’s will, signed 9 Mar. 1792, probated 12 July 1794, Public Record Office, National Archives, Prob 12/1247. He died on 2 May 1794. He used the same expression for his estates in the county of Huntington: “at the time of my decease unto the person or persons who shall upon my death succeed or become entitled to those estates.”

Frederick Cavendish’s will, signed 24 Jan. 1797, probated 29 Oct. 1803, Prerogative Court of Canterbury, PROB 112/1399/369.

The 1803 land tax return was dated 7 July. The 1804 land tax return was dated 28 June. George Augustus Henry Cavendish’s name is listed from 1804 through the year of Henry Cavendish’s death, 1810, and beyond. Lancaster County Archives, QDL/LN/23.

From his conversation with Barrow, it seems that Cavendish knew the manor and its setting. Possibly his father brought him there on one or more of his visits. In 1786, on a journey with Blagden, he passed into Cumbria, but there is no mention of Holker Hall. Blagden to Banks, 4 Sep. 1786.

The documents are in Devon. Coll., L/36/62.

Henry Cavendish, “Walnut Cabinet in Bed Chamber,” Devon. Coll.

Henry Cavendish, “List of Papers Classed,” ibid.

Henry Cavendish, “Keys at London,” ibid.